Buckminster Fuller, Literary Critic

Among the many uncollected works of Buckminster Fuller are his book blurbs. There was a time when Fuller’s social credit was such that an advertiser would use his words to promote anything from books on architecture to non-fiction to novels. Here are some examples of book and magazine blurbs by R. Buckminster Fuller. - Trevor Blake

Architects on Architecture by Paul Heyer. “Your beautiful book is magnificently done.” New York Times 26 February 1967. Paul Heyer is an architectural critic and author.

Future Shock by Alvin Toffler. “Cogent… brilliant… I hope vast numbers will read Toffler’s book.” Made into a film narrated by Orson Wells. New York Times 5 January 29 and 31 August 1970. Alvin Toffler, like Fuller, was associated with Fortune magazine. Toffler is the author of The Third Wave and other books on futurist themes.

Watership Down by Richard Adams. “One of those great ones that every once in a while lets us know that the universe has something really mysteriously great ‘going’ for humanity.” Watership Down was made into film and a television series. New York Times 26 February 1974.

Naked is the Best Disguise by Samuel Rosenberg. The author “may overwhelm you. His tapestry is beautiful. It is incredibly logical. I love it.” New York Times 16 and 20 June 1974. Rosenberg suggests that author Sir A. C. Doyle revealed his personal thoughts through his character Sherlock Holmes.

The New Yorker Magazine. “I first came to Philadelphia in the navy, during World War I. I was the commander of a small craft and was ordered to dock at the foot of Market Street. It happened to be Halloween. Not knowing how Philadelphia behaves on Halloween, I was astonished to find the whole evening I was kissed by beautiful girls. They still have this wonderful community spirit here in Philadelphia.” New York Times 24 October 1974. The New Yorker is a magazine founded in the 1920s.

The Urban Predicament by William Gorman and Nathan Glazer. “I am in full agreement with you regarding the predicament… and I am all for the logical amplification of concern so effectively accomplished by your book.” New York Times 13 June 1976. A publication of the Urban Institute, founded in 1968.

The Human Cougar by Lloyd L. Morain. “… a warm, vivid appreciation of… a disappearing species… maligned by the masters of money and politics… ” New York Times 21 November 1976. Morain is also the author of the book Humanism As the Next Step.

Others Including Morstive Sternbump by Marvin Cohen. “This book appeals to me so much that I do not want to make any careless quickie remarks. Morstive Sternbump’s philosophy is congruent with my own.” New York Times 12 December 1976.

The Clam Lake Papers by Edward Lueders. “So spontaneously of interest that despite the priorities, we find ourselves stealing time that belongs to our committed responsibilities. The Clam Lake Papers… certainly are for me.” New York Times 27 November 1977. Lueders is also the author of Writing Natural History.

The Cousteau Almanac by Jaques-Yves Cousteau. “The Cousteau Almanac is must reading for all those committed to the successful continuance of humankind in the Universe.” New York Times 25 October 1981. Cousteau was the inventor of the self-contained underwater breathing apparatus, SCUBA.

Mankind in Amnesia by Immanuel Velikovsky. “Mankind in Amnesia is an extraordinarily important book, beautifully researched and devastatingly true.” New York Times 11 April 1982. Velikovsky was the founder of what has been called catastrophism, or the interpretation of ancient stories of world catastrophes as literal descriptions of past events.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

Buckminster Fuller and the Homeless of New York

If Buckminster Fuller is known for any effort, it is the effort to provide shelter. But who did Fuller actually provide shelter for? The Lightful House and 4D House existed only on paper. The Dymaxion House existed only as a small scale model. The Dymaxion / Wichita House existed as two full-scale models (one internal, one external, neither able to be connected to the other). The Dymaxion Deployment Unit did house a small number of US armed forces personnel but the DDU was the invention of Victor C. Norquist, not Buckminster Fuller. The geodesic dome was invented by Walter Bauersfeld. Of the dozens of books by and about Fuller, of the thousands of articles on his life and work, most of them fail to give a single instance of when Fuller actually provided shelter to anyone. The Buckminster Fuller Bibliography by Trevor Blake is the first book to document that Fuller provided shelter for others with his own direct effort.

The New York Times for 10 September 1932 includes an uncredited article titled “Single Jobless Men to Get Lodging House / Social Worker and Engineer Obtain Use of Tenement for Those Ineligible for City Aid.” The building in question was a then-deserted seven-story building located at 145 Ridge Street in New York City, New York. The social worker was Ben Howe and the engineer was Buckminster Fuller. Fuller is described as “editor of the magazine Shelter and head of Structural Study Associates, an engineering firm.” According to the article, the men who were renovating the building were hoping to live in it afterward. They were otherwise ineligible for benefits because they were not the head of a family. The building was to house two hundred and fifty men at a time and serve several thousand during Winter. Lieutenant R. E. Johnson was also involved in this project. He is described as a “former army construction engineer and commander of the United States Ex-Service Men’s Association.” At the time of the article, the shelter was under construction. The building described in this article no longer exists.

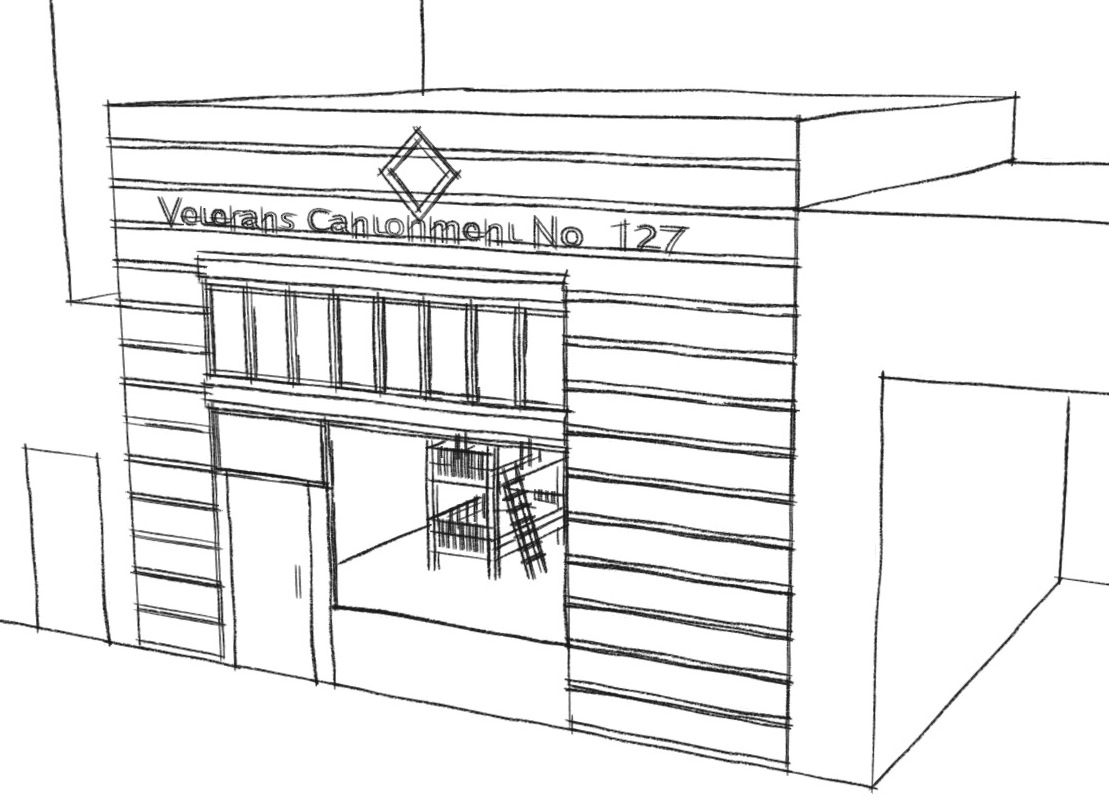

The New York Times for 2 December 1932 includes an uncredited article titled “Jobless Veterans Back in Barracks / 300 Single Men to Live Under Military Rule in Converted Clubhouse in 54th St.” The building in question was a five-story converted boy’s club at 340 East 54th Street in New York City, New York. According to the article, the shelter would be run by and for veterans and in a military style. The shelter would serve single men because of their difficulties in obtaining relief from existing services. The plan was initiated by a meeting of representatives of various interested organizations at the office of Raymond V. Ingersoll. Ingersoll served as a New York Parks Commissioner and as a Brooklyn Borough President. A residential development named after Ingersoll stands today at 120 Navy Walk in Brooklyn, New York. The representatives at the meeting included Ben Howe and Buckminster Fuller of the 145 Ridge Street shelter, Philip Hiss, Colonel Walter L. DeLamater, Arthur Huck, Louis Gleich, Owen R. Lovejoy, Cyrus C. Perry, James R. Sichel and Henry C. Wright. Philip Hiss went on to design and build homes in Florida, although he was not a trained architect. Col. DeLamater served in the 71st Infantry Regiment, an organization of the New York State Guard. Arthur Huck worked on numerous homeless shelter projects in the New York area, as reported in decades of articles found in the New York Times. Louis Gleich was a commander in the New York County Council of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and was the chairman of the committee that erected a VFW monument in Union Square. Owen Lovejoy served as the General Secretary of the National Child Labor Committee. The building formerly housed the Kips Bay Boys’ Club, where Lovejoy served as secretary. The building was to be called Veterans Cantonment No. 1. At the time of the article, the shelter was in operation. The building described in this article may still exist, next to the building that currently is designated as 340 East 54th Street.

By 1932, Buckminster Fuller had published drawings of his 4D House and exhibited models of his Dymaxion House. He had been featured in the Chicago Evening Post, Fortune Magazine, the Harvard Crimson, Modern Mechanics Magazine, the New York Times and Time Magazine. Fuller had published his monograph 4D and was publishing Shelter Magazine. He had earned the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade in the United States Navy. In 1933 Fuller would begin work on the Dymaxion Car.

What makes these homeless veteran shelters distinct from any other that Fuller was involved with was that they provided actual shelter to actual men. While they do not have the glamor of Fuller’s Dymaxion House and other creations, they hold the advantage of having existed. Giving a new purpose to an existing structure was an idea that Fuller seldom developed but never abandoned. In his 1970 book I Seem to Be a Verb, Fuller wrote: “Our beds are empty two-thirds of the time. Our living rooms are empty seven-eights of the time. Our office buildings are empty one-half of the time. It’s time we gave this some thought.”

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

Reference:

71st Infantry Regiment (New York). 1 April 2009. Wikipedia. 22 May 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/71st_Infantry_Regiment_(New_York)

Davis, Edwards: “Advocates the Standardizing of Industry by Law.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 27 July 1913: SM14

Fuller, R. Buckminster. I Seem to Be a Verb. New York: Bantam Books, 1970.

Ingersoll, Raymond V. Houses. 2009. New York City Housing Authority. 22 May 2009. http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/developments/bklyningersoll.shtml

“Louis Gleich, 69, Dies.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 26 Sept 1961: 39.

“Philip H. Hiss 3d, 78, Designer of Buildings.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 4 November 1988: B4.

Sieden, Lloyd S. Buckminster Fuller’s Universe. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing, 1989.

The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller (Part 3 of 3)

The Lost Inventions of R. Buckminster Fuller is a three-part investigation into the inventions of Buckminster Fuller. These essays can serve as companion essays for two previous books by and about Fuller: Inventions (Fuller, St. Martin’s Press 1983) and The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (Marks and Fuller, Doubleday 1973). Ownership of these two books is not necessary for reading these essays. Page numbers without citations are from Inventions Fuller made many claims about his inventions, claims which are confirmed or called into question by these essays. A new appreciation for Fuller’s innovations is the result.

Fuller claimed that his life goal was to provide humanity with the means to save itself from itself and from natural disasters. To that end Fuller could have given his inventions up to the public domain, making them more accessible to more people. But Fuller sought, obtained and defended patents for many of his inventions, for two reasons.

First, Fuller hoped that the long-term and public nature of the US Patent Office would serve as a long-term and public record of his work. Fuller wrote in Inventions: “The public record established by my patents […] can serve as a critical appraisal of the historical relevance, practicality, and relative effectiveness of my half-century’s experimental commitment to discover what, if anything, an individual human being eschewing politics and money-making can do effectively on behalf of all humanity.”

Second, Fuller hoped to prevent others from profiting from his inventions. Donald W. Robertson served as Fuller’s patent attorney and wrote about his experience in The Mind’s Eye of Buckminster Fuller (Robertson, St. Martins 1983). Robertson described why Fuller sought patents: “While Fuller did not wish to seek patent profits by selling efforts, he was adamant in seeking to forestall efforts of others to profit by making unauthorized use of his inventions.” Fuller defended his patent interests. Fuller’s archive includes legal disputes over royalties with North American Aviation between 1958 and 1961 and with Ernest Okress between 1978 and 1979. According to Siobhan Roberts’ book on mathematician Donald Coxeter, King of Infinite Space (Roberts, Walker & Co. 2006), Fuller’s patent on the Radome was defended in Canada by the United States Department of Defense. Fuller sought and sometimes obtained intellectual property rights in Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Columbia, The Congo, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Finland, France, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United State, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Venezuela and West Germany.

All of Fuller’s inventions are lost in some way. All of Fuller’s U. S. patents are lost in that they have expired. Some of Fuller’s patents expired in his lifetime. This is due to his being unable to afford a renewal, or his deciding to let a patent expire, or perhaps neglect. Many of Fuller’s patents lost their references to earlier patents by other inventors. That is, what Fuller claimed he invented was in fact invented by someone else. Sometimes Fuller was ignorant of prior work, such as the octet-trus constructions of Alexander Graham Bell. Sometimes Fuller stole ideas whole-cloth, such Kenneth Snelson’s sculptures re-branded as Fuller’s tensegrity. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they have yet to go into production, existing only as scale models. Perhaps now that Fuller’s patents have expired some of them can be tested against Fuller’s claims. Perhaps the fog gun could be tested in arid environments, for instance. Many of Fuller’s patents are lost to the curious because they are not always filed under their popular name. The patent for the geodesic dome is to be found under the title ‘Building Construction,’ which has likely caused some researchers difficulty in finding it. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they are under-documented. Automobile restoration firm Crosthwaite and Gardiner had access to nearly all the information ever produced about the Dymaxion Car, but at times had to make their best guess in the creation of Dymaxion Car #4 because detailed schematics and photographs were not available. The credits to many of the illustrations in Inventions are lost. Illustrations appear in the book without further information. The photograph on the front cover is a 36-foot geodesic dome made by students at the University of Minnesota and assembled in Aspen, Colorado in 1952. Additional photographs of this dome can be found in Dymaxion World illustrations 334-339. The end papers show the paperboard dome of 1954. Page vi shows Fuller with a partially-assembled model of the 4D House in New York City in 1929. Page xi shows Fuller at Black Mountain College in 1948. Pages xvii and xviii appear to be Fuller at the Montreal World’s Fair dome. The photographs on pages xiv, xxvi-xxvii, xxxi and xxxii are of unknown origin.

Tetrahedron City is a floating city proposed by Fuller in the early 1960s and described in Dymaxion World. Fuller never sought a patent for Tetrahedron City. Tetrahedron City is an equilateral tetrahedronal city two miles long at its base edge, housing one million people in three hundred thousand apartments. Each apartment would have an ocean front balcony. City infrastructure is located in the interior of the tetrahedron, airstrips are located along the base exterior. The foundation of Tetrahedron City is made up of hollow box-sectioned reinforced concrete, providing buoyancy. The size of the city provides stability even in ocean storms.

Tetrahedron City would be slightly more than 1.6 miles in height. This is three times the height of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, the tallest man-made habitat in history as of 2012 at 2,723 feet. Tetrahedron City would have an overall population comparable to Calgary, Canada and a population density comparable to Hong Kong, China. Tetrahedron City would be significantly more spacious and less populated than New York City, New York or Mexico City, Mexico. These cities have challenges but they cannot be said to be failures. The Robert Taylor Homes of Chicago, Illinois, however, were not able to meet their challenges. The Robert Taylor homes included two miles of housing spread among twenty-eight buildings, each sixteen stories in height. The Robert Taylor homes housed up to 27,000. In short order, these buildings became so rife with violence, poverty, arson and drug abuse that the only solution to these problems was to re-locate the residents and demolish the buildings. A similar outcome occurred in the Cabrini-Green buildings, also located in Chicago. The problems of these buildings were blamed both on gangs and a lack of green space or private space. How Tetrahedron City might address these problems remains to be determined.

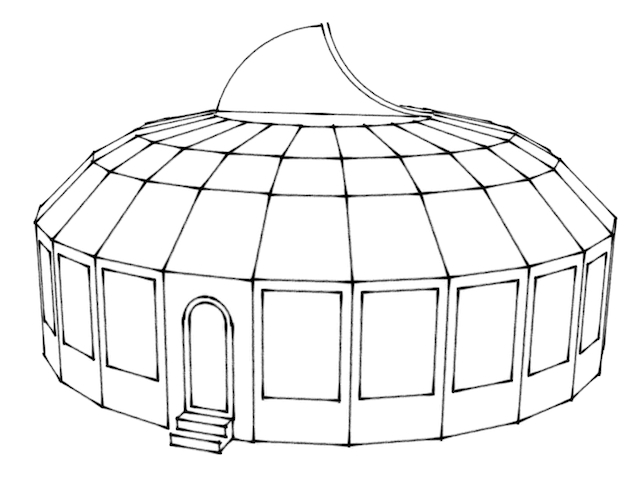

Triton City is a floating city proposed by Fuller in the early 1960s and described in Dymaxion World. Fuller never sought a patent for Triton City. Triton City was designed to house up to five thousand people in one-fourth of a square mile, approximating the population of a small town under one roof. Triton City was to be a proof-of-concept module for the eventual creation of Tetrahedron City. The patron for Triton City was Matsutaro Shoriki. Shoriki is considered the father of Japanese professional baseball, and was the owner of newspapers and television stations. He was also considered the father of Japanese nuclear power, was under the pay of the Central Intelligence Agency to establish pro-USA television stations, and was a Class-A war criminal. Shoriki died after commissioning Fuller to design Tetrahedron City.

Fuller proposed the World Game in 1961 while lecturing at Southern Illinois University. The World Game was played on a large scale Dymaxion map representing Earth with students representing the population of the world. The goal of the game is to provide advanced access to goods and services to all people without resorting to war. The rules of the game are based on information on goods, services and transportation available to the World Game Institute. The information-gathering phase of the World Game echoes Fuller’s survey of industry from decades earlier. World Game has been played by students around the world to varying degrees of success. By the early 2000s the intellectual property of the World Game Institute had been purchased by O.S.Earth.

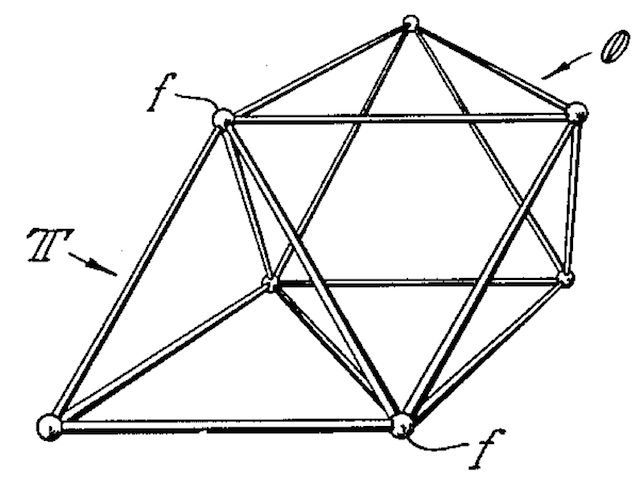

The Octet Truss is a building component made up of a tetrahedron and an octahedron with equal edge lengths. The Octet Truss is called Synergetic Building Construction in patent 2,986,241 (30 May 1961). Canadian patents were awarded in 1957. Grunch of Giants claims the Octet Truss was designed in 1933 and prototyped in 1949. Fuller claims that he owned a trademark, copyright and patent on the octet truss and that this was granted in part because he had shipped the structure across state lines. Shipping an invention across state lines is not a prerequisite for being granted a patent. In Genius At Work: Images of Alexander Graham Bell by Dorothy Harley Eber, Fuller claims to have been unaware of Bell’s octahedron-tetrahedron towers and kites. Bell was granted patent 856,838 for Connecting Device for the Frames of Aeriel Vehicles and Other Structures on 11 June 1907. This patent shows an modular octahedral-tetrahedral system “adaptable to a great variety of structural uses.” The octet truss is in use in the International Space Station, as Fuller claimed it would be. Closer to home, lighting rigs in theaters often use an octet-truss structure.

The Octet Truss is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them.

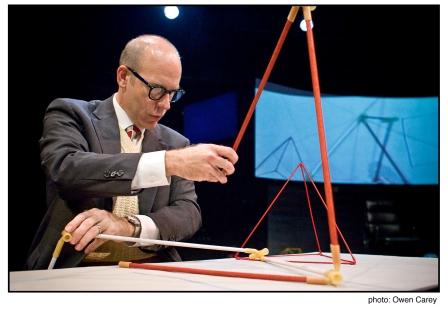

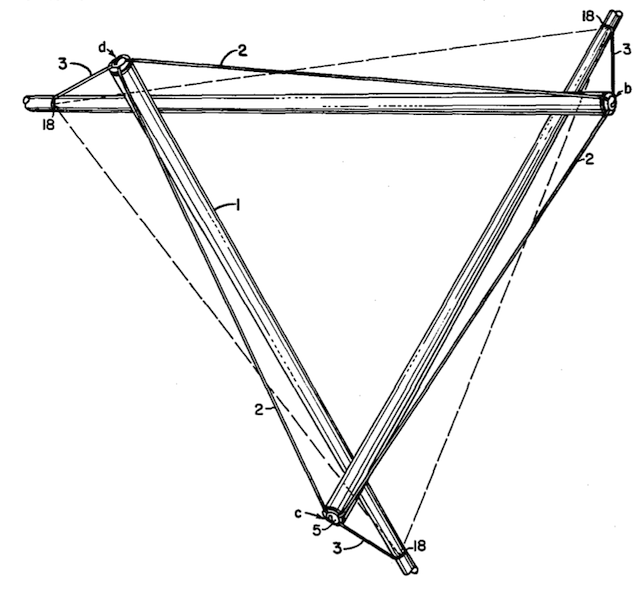

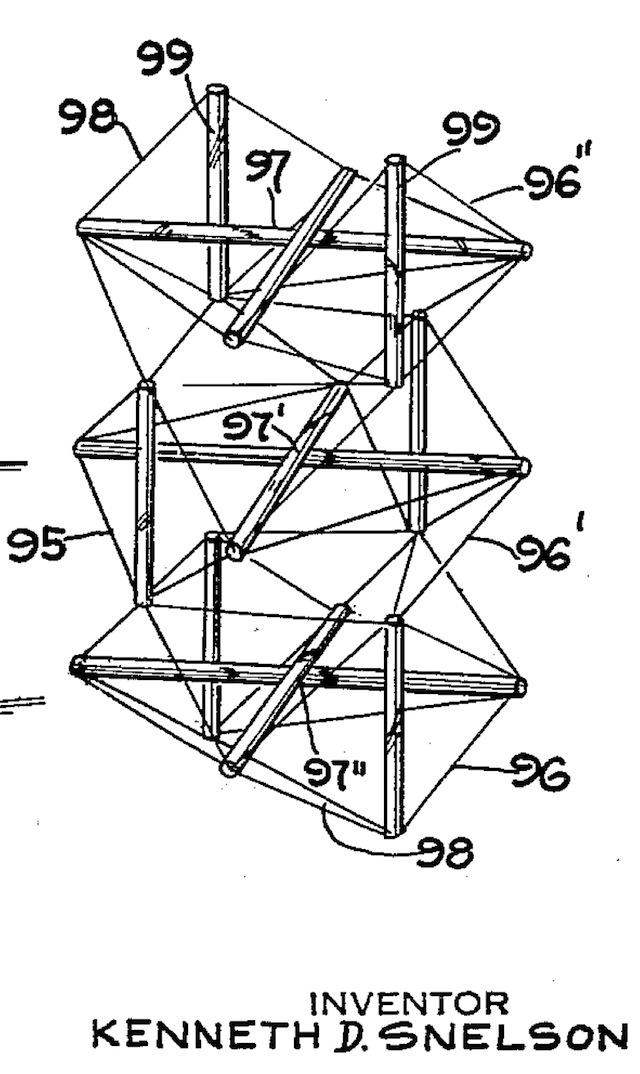

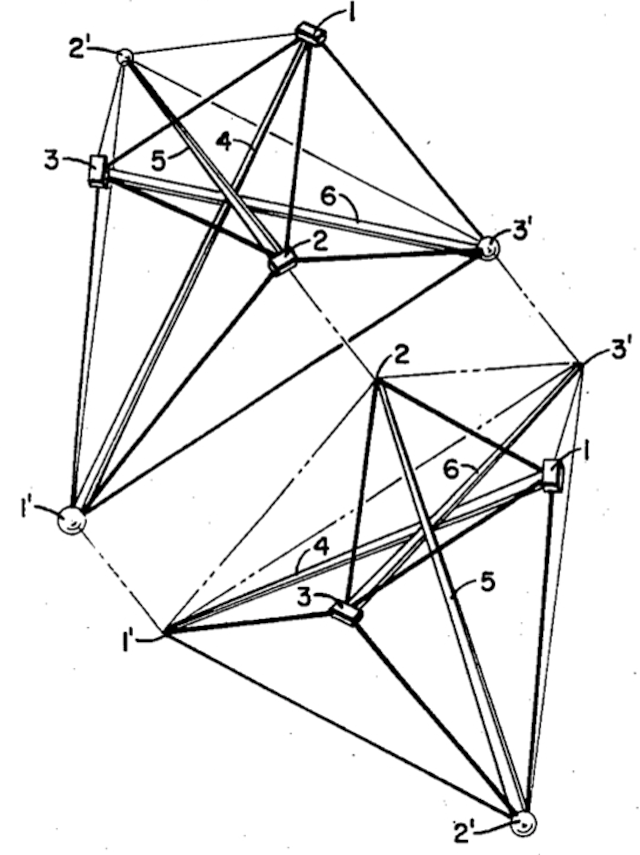

Tensegrity is a form of sculpture in which flexible wires are held taunt by struts, and the struts are held in place by the wires. Tensegrity is called Tensile-Integrity Structures in 3,063,521 (13 November 1962). Non-Symetrical Tensegrity is called Non-Symetrical Tension-Integrity Structures in 3,866,366 (18 February 1975). Canadian patents were awarded in 1960. Non-symetrical Tensegrity was patented in Canada, Great Britain, India, Italy and Japan in 1977. In Grunch of Giants, Fuller claims to have designed tensegrity in 1929. Buckminster Fuller invented the word tensegrity, but the structure described as a tensegrity was invented by Kenneth Snelson. The November 1990 issue of International Journal of Space Structures magazine includes a letter to the editors from Snelson on his sculptures and Fuller’s seizure of them.

When we got together again in June [1949] I brought with me the plywood X-Piece. When I showed [Fuller] the sculpture, it was clear from his reaction that he hadn’t understood it from the photos I had sent. He was quite struck with it, holding it in his hands, turning it over, studying it for a very long moment. He then asked if I might allow him to keep it. […] That original small sculpture disappeared from his apartment, so he told me at the end of the summer. [In] January 1951 he published a picture of the structure in Architectural Forum magazine and, surprisingly, I was not mentioned. When I posed the question some years later why he accredited me, as he said, in his public lectures and never in print, he replied, ‘Ken, old man, you can afford to remain anonymous for a while.‘

The two tensegrity patents in Inventions cite Dymaxion World, and illustration 265 in Dymaxion World mentions Snelson. The sculpture on page 179 was made by students at the University of Oregon in 1959. The sculpture on pages 184-185 was made by students at North Carolina State College in 1950. The sculpture on page 190 is claimed to have been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1959 but perhaps instead it was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in that same year, along with a geodesic dome and octet trus sculpture. At no time has a tensegrity been been as a shelter. Not for a home, a bridge, a garden shed, a bird house or any other sort of shelter. Tensegrities are fascinating sculptures but so far have no use in architecture.

Tensegrity is preceded by the sculptures of Kenneth Snelson, and Fuller was entirely aware of it.

The Geoscope was discussed in Fuller’s 1962 book Education Automation. The Geoscope was a proposed two-hundred-foot diameter sphere suspended by cables and covered in computer-controlled electric lights. Viewers outside or inside the Geoscope could see representations of migrations of people, goods and services on this miniature Earth. As with the Dymaxion Map, Fuller hoped that viewing the Earth as a whole would inspire whole-earth thinking rather than nationalist thinking.

Fuller never sought a patent for the Geoscope. It is preceded by the patent Exhibition Structure 655255 by Herbert P. W. Lyouns, awarded 7 August 1900. Exhibition Structure was a large globe covered in electric lights. Viewers outside or inside the Exhibition Structure could see representations of migrations of people, goods and services on this miniature Earth. Lyouns wrote: “The space within the globe will be divided by suitable partitions into rooms hallways and exhibition booths or apartments and an important feature of the invention is to locate these various rooms and apartments in such relation to the outlines on the outer surface of the globe as to permit the products of any particular country or city to be exhibited adjacent to the location of such country or city upon the map delineated upon the surf arc of the globe. Thus an important educational result is accomplished the visitor being enabled to associate in his mind the peculiar products of different countries with the geographical locations of such countries.”

The Geoscope is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication Fuller was aware of them.

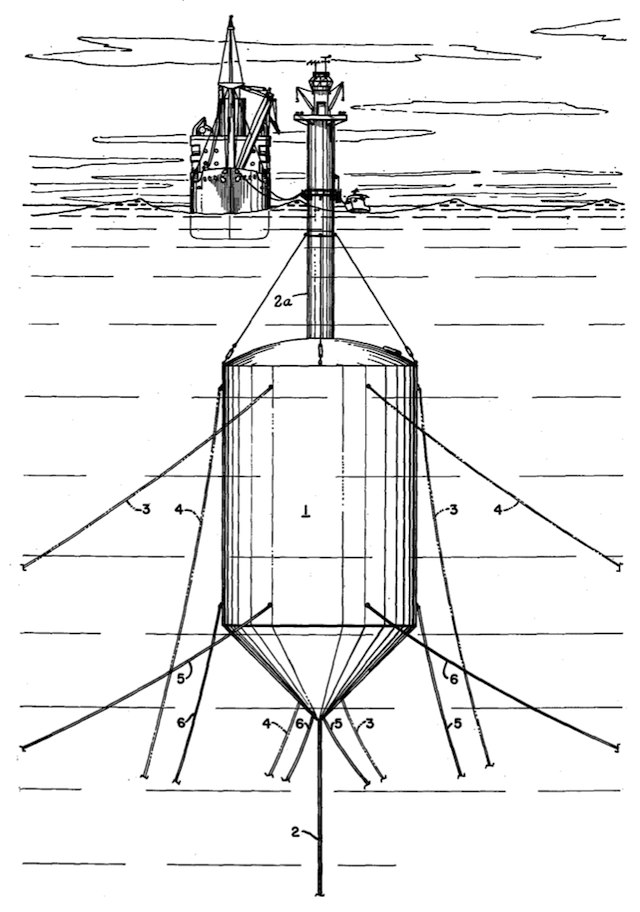

The Submarisle (Undersea Island) is a buoyant underwater shelter anchored by cables to the sea floor. The Subgarisle is called an Undersea Island in patent 3,080,583 (12 March 1963). Jacques Cousteau’s Conshelf One housed two researchers for seven days in 1962, and Conshelf Two housed ten researchers for thirty days in 1963. The Submarisle is distinctive from Cousteau’s habitats in that it is buoyed on triangulated lines rather than resting on the sea floor. The Submarisle floats upward on three wires as Fuller’s Hanging Storage Shelf Unit hangs down from three wires.

The world has yet to see giant cargo submarines in need of submarisle docks. But drug runners are using very small submarines to transport their goods in the early 21st Century. Perhaps there are illegal and hidden submarisles in the world.

The Submarisle is the invention of Buckminster Fuller.

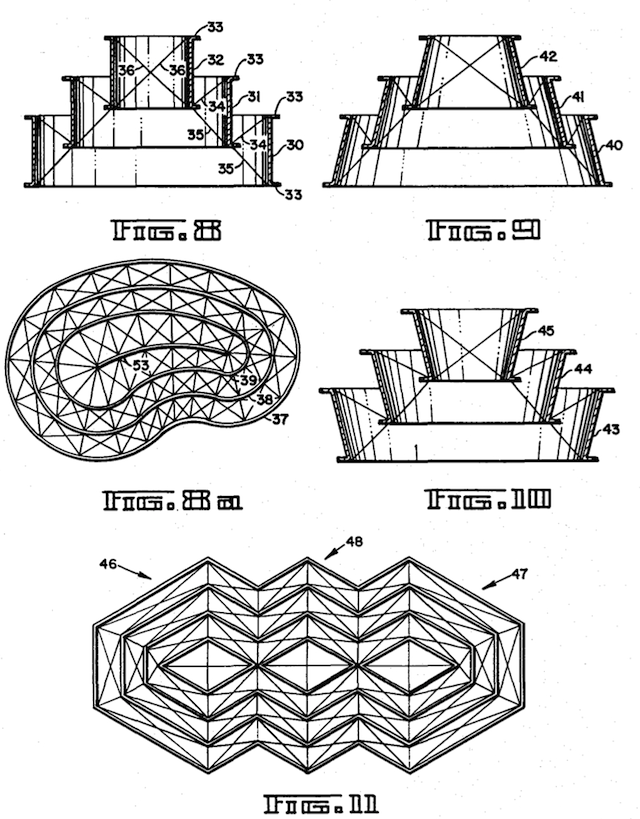

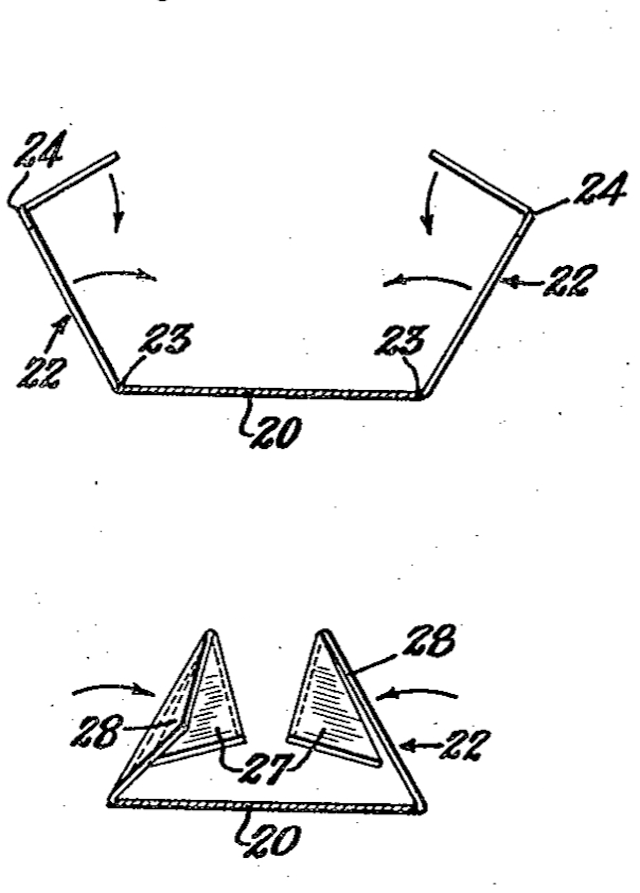

The Aspension (Suspension Building) is an architectural technique in which higher-up components are suspended by lower-down components. The Aspension Building is called a Suspension Building in patent 3,139,957 (7 July 1964). This is another invention by Fuller that has never been utilized commercially, although aspension structures exist as models.

The Aspension Suspension Building is a form of the sculptures of Kenneth Snelson, and Fuller was entirely aware of it.

The Octa Spinner (circa 1965) is a means of weaving tensegrity structures. The Octa Spinner has no patent. In Inventions, Fuller writes: “I did not go through with the octet spinner patent after filing because the expense of patent work is very great, and I’m not in the manufacturing world, and I felt that it would not be worth carrying any further.” The Mind’s Eye of Buckminster Fuller, however, claims that Fuller’s initial application was rejected and that he only ended the process after carrying it further into a second application. The Stockade patents are part of the manufacturing world, and much of his work on shelters could be considered the same. The Chronofile contains a folder labeled “Original Patents file: Octa Spinner (application withdrawn - case no. 349.021) March, 1965.”

The Star Tensegrity (Octahedral Truss) is a variety of tensegrity. The Star Tensegrity is called an Octahedral Building Truss in patent 3,354,591 (28 November 1967). Canadian patents were awarded in 1968. The photograph on page 248 shows the Union Carbide Tank Car Company Dome in Baton Rouge, LA USA. This dome was constructed in 1958 and demolished in 2007. The Octa-Hedronal Truss received a patent in Japan in 1965.

Tensegrity is preceded by the sculptures of Kenneth Snelson, and Fuller was entirely aware of it.

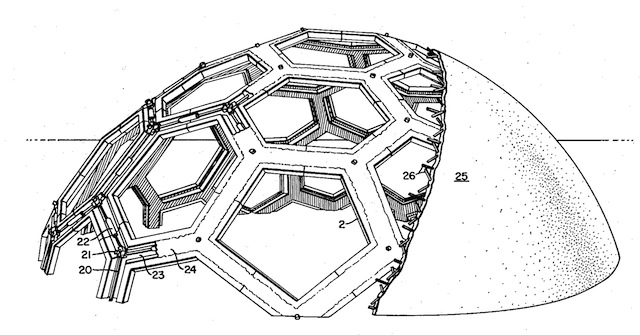

The Monohex (Geodesic Structures) is a variety of geodesic dome, made up of alternating hexagons and pentagons. The Monohex is called Geodesic Structures in patent 3,197,927 (3 August 1965). The photograph on pages 216-217 show the 50-foot Fly’s Eye dome built by John Warren. Additional photograph of this dome can be found on pages 210-211 of Buckyworks by J. Baldwin. The photographs on pages 222-223 are of unknown origin. The Monohex Geodesic Structure received a patent in Japan in 1979.

The Monohex Geodesic Structure, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. But the reduction of dome components to stackable interchangeable modules is a form unique to Fuller.

The Laminar Dome is a variety of geodesic dome, made up of alternating diamond shaped panels. The Laminar Dome is called a Laminar Geodesic Dome in patent 3,203,144 (31 August 1965). Canadian patents were awarded in 1961. The photograph on page 229 shows the same radome in illustration 415 of Dymaxion World, built by Western Electric.

The Laminar Dome, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. But the woven construction of this dome is a form unique to Fuller.

Energy Storage / Switching 1968-1969 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

Electronic Computer Energy Transformation 1969-1972 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

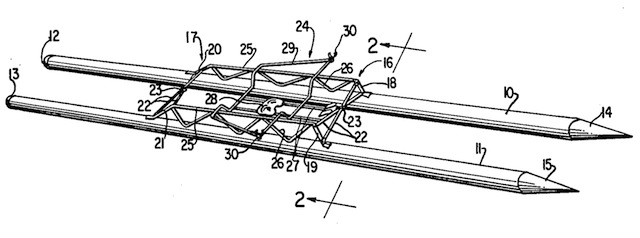

The Rowing Needles (Watercraft) is called a Watercraft in patent 3,524,422 (18 August 1970). Inventions does not give the filing date, which was 28 March 1968. In Dymaxion World illustration 298 this is called a minor invention of 1947. In Grunch of Giants, Fuller claims the rowing needles were invented in 1938 and prototyped in 1954.

Catamarans and outrigger canoes have existed since antiquity. As an avid sailor, Fuller would have been familiar with these crafts.

Cloud Nine is a floating city proposed by Fuller in Dymaxion World, published in 1973. Fuller never sought a patent for Cloud Nine. Fuller proposed that the air inside a one-mile-diameter geodesic sphere would weight more than the sphere itself. Sunlight would heat the surface of the sphere, heating the air inside, causing a temperature difference of the air inside and outside the sphere, and by this means the sphere would float upward. Fuller proposed many thousands of people could live in such a floating city, allowing it to drift or be guided.

The first manned hot air balloon (drifting) was demonstrated 1783 by the Montgolfier brothers. The first thermal airship (guided) was demonstrated in 1973, the year Dymaxion World was published. Stories of a city in the sky are found in antiquity. The Cloud Nine geodesic sphere, as a geodesic sphere, is preceded by similar inventions. But Buckminster Fuller’s Cloud Nine is an original proposal for how a floating city might be made.

Tiago Barros made a similar proposal nearly forty years later with his Passing Cloud.

The Passing Cloud is an innovative and environmentally friendly method of transportation that doesn’t require expensive steel tracks or concrete highways. It is made of a series of spherical balloons that form the shape of a cloud. Its inner stainless steel structure is covered with heavy weight tensile nylon fabric. During the journey, It moves according to prevailing winds speed and direction at the time of travel. Since it moves with the wind, no wind is ever felt during the trip, offering the passengers a full ‘floating sensation.’

Metabolics Money 7/11/1973 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

The Geodesic Hexa-Pent is called a Geodesic Pentagon and Hexagon Structure in patent 3,810,336 (14 May 1974). The patent was granted to Shoji Sadao and assigned to Fuller & Sadao, Inc. The Hex-Pent Dome was patented in Australia, Canada, India, Israel and Italy in 1973. Shoji Sadao was a former student of Fullers. Sadao was involved in the creation of the icosohedral Dymaxion Map (known as the Raleigh projection) and in the creation of the Expo ’67 dome in Montreal. In Inventions, Fuller claims that the Hexa-Pent dome was developed by Sadao and jointly named by Sadao and Fuller. The Hexa-Pent dome is preceded by patent 3,114,176 of Alvin E. Miller (17 December 1963).

The Geodesic Hexa-Pent dome, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. This patent was never claimed by Fuller. The Hexa-Pent dome was featured in the May 1972 issue of Popular Science magazine. The plans for the dome advertised on page 139 of this issue represents the only time Fuller himself sold dome instructions to the general public.

Helicopter Rotor Sail 1976 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

Fuller’s name for his thoughts was synergetics. Synergetics is a system of mathematics, an ethical system, a philosophy, an aesthetic, a form of poetry and more. Synergetics is the central invention of Fuller, with all the individual artifacts only special cases of synergetics. Hugh Kenner wrote that synergetics puts Fuller in the transcendentalist school, with his ancestor Margret Fuller. Elements of synergetics appear in Fuller’s earliest lectures and writing, but the 1975 publication of Synergetics can be considered a first full statement of his intent.

Fuller discovered a formula for predicting the number of spheres found in the outer shell of closest-packed spheres. That formula is ten times f squared plus two, with f equal to the frequency (number of layers). One sphere can be most closely surrounded by twelve identical spheres; six around the first sphere’s equator, three nestled underneath and three nested on top. This comprises the first layer, thus ten times one square plus two equals twelve, the number of spheres surrounding the original sphere. A second layer will have 43 spheres, a third will have 92 spheres, and so on. Fuller’s formula can predict the number of spheres on the outer shell of any array of closest-packed spheres.

Fuller formalized his Primitive Hierarchy of shapes in Synergetics 988.20 (1975, 1979). Fuller began with the claim thoughts are made up of ideas and that these ideas are spherical in shape. One idea is insufficient to form a thought, as would be two. Three ideas are close to a thought, but the connection between them has surface but no volume. Four spherical ideas packed together form a tetrahedron, a shape that has volume. Thoughts, therefore, are shaped like tetrahedrons. Fuller claimed that for this reason tetrahedrons were primal shapes and a more worthy basis for mathematics than cubes, grids or other systems.

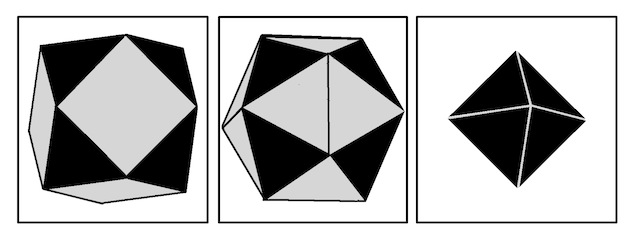

If the volume of a tetrahedron is equal to one, then other shapes can be assigned volume in relation to the tetrahedron. The next larger shape in the Primitive Hierarchy is the cube. The volume of a cube is obtained by using the dual of the tetrahedron. To obtain a dual of a shape, make new edges at right angles to the center of the edge of a shape. The duel of a tetrahedron is another tetrahedron. The vertices of a tetrahedron and its duel form a cube. That cube will have a volume of three. The duel of that cube will form an octahedron with a volume of four. The duel of that octahedron will form a rhombic dodecahedron with a volume of six. These four shapes are a sufficient introduction to the Primitive Hierarchy, although Fuller identified larger and smaller shapes in the series.

Johannes Kepler proposed a different concentric hierarchy of shapes in his 1596 book Mysterium Cosmographicum. Kepler used the platonic solid shapes, and arranged them from (smallest to largest) as octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron and cube. The idea of arranging shapes within other shapes is an ancient one. The Primitive Hierarchy is preceded by similar inventions. The Primitive Hierarchy is unique to Fuller.

The Floating Breakwater is patent 4,136,994 (4 February 1975) and the Floatable Breakwater is patent 3,863,455 (30 January 1979). These are breakwaters that float on the surface of the ocean to control the movement of the water or contaminants in the water. Fuller claims that he produced Floatable Breakwaters but there are no photographs of them in Inventions. Inventions does not give the filing date for either of these patents, which were 10 December 1973 and 19 September 1977 respectively. Dozens of floating breakwater patents, some generating power like Fuller’s Floatable Breakwater, predate Fuller’s patents. Lancelot Kirkup was granted patent 226,663 for his breakwater “loaded so to float that its greatest diameter will be about at the water line” on 20 April 1880.

The Floating Breakwater and Floatable Breakwater are preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them.

The Tensegrity Trus is a variety of tensegrity. The Tensegrity Trus is called a Tensegrity Module Structure and Method of Interconnecting the Modules in patent 4,207,715 (17 June 1980). The patent was granted to Christopher J. Kitrick. Fuller wrote in Inventions: “I authorized Chris to take out a patent on his invention, which by agreement I paid for and on the basis it be assigned to me.” Fuller is not listed as assignee in this patent.

Tensegrity is preceded by the sculptures of Kenneth Snelson, and Fuller was entirely aware of it.

De-Resonated Tensegrity Dome 1981 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

Methods and Apparatus for Constructing Spheres 7/1/1982 is found in the Chronofile, housed at Stanford University. This is an invention in progress that is not otherwise documented.

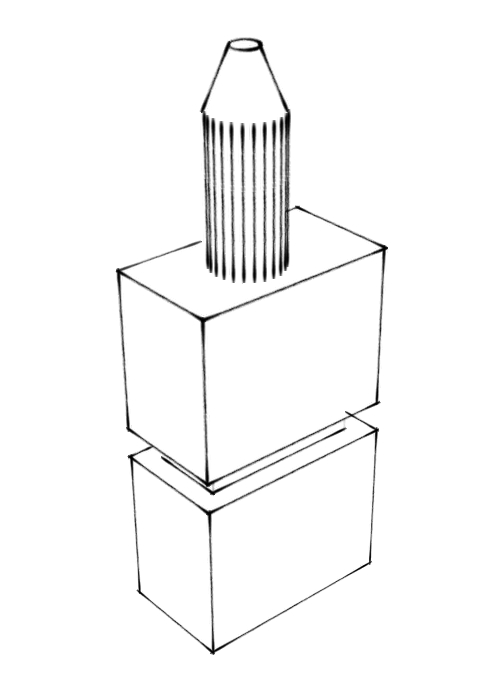

The Hanging Storage Shelf Unit is a shelf suspended from the ceiling. The Hanging Storage Shelf Unit is patent 4,377,114 (22 March 1983). Inventions does not give the filing date, which was 5 October 1981. Fuller claims the hanging storage shelf unit was built and used in a bookstore, perhaps the unit shown in the photograph on page 295. The book on the shelf in that photograph is Dymaxion World thus the photograph could have been taken no earlier than 1973. The hanging storage shelf unit is not unlike the 1944 criss-cross tensionally supported table found in illustration 300 in Dymaxion World.

Patent 1,5952,466 (27 March 1934) was awarded to Alexander Sjodin, Charles J. Olund and Robert J. Moody. This patent is cited in Fuller’s patent for the Hanging Storage Shelf Unit. This Display Rack was suspended from above. Theodore Pollard was awarded patent 3,866,364 (18 February 1975) for Modular Structure for Use in Merchandising Operations. This consists of a hexagonal shelf that can be hung by wires.

The Hanging Storage Shelf Unit is preceded by similar inventions, and Fuller was aware of at least one of them.

Conclusion

R. Buckminster Fuller described himself as a “terrific package of experiences.” The record of Fuller’s uncredited duplication of prior work suggests that he was at times a terrific package of other people’s experiences. The greatest invention of Richard Buckminster Fuller was the character Bucky.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller (Part 2 of 3)

The Lost Inventions of R. Buckminster Fuller is a three-part investigation into the inventions of Buckminster Fuller. These essays can serve as companion essays for two previous books by and about Fuller: Inventions (Fuller, St. Martin’s Press 1983) and The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (Marks and Fuller, Doubleday 1973). Ownership of these two books is not necessary for reading these essays. Page numbers without citations are from Inventions Fuller made many claims about his inventions, claims which are confirmed or called into question by these essays. A new appreciation for Fuller’s innovations is the result.

Fuller claimed that his life goal was to provide humanity with the means to save itself from itself and from natural disasters. To that end Fuller could have given his inventions up to the public domain, making them more accessible to more people. But Fuller sought, obtained and defended patents for many of his inventions, for two reasons.

First, Fuller hoped that the long-term and public nature of the US Patent Office would serve as a long-term and public record of his work. Fuller wrote in Inventions: “The public record established by my patents […] can serve as a critical appraisal of the historical relevance, practicality, and relative effectiveness of my half-century’s experimental commitment to discover what, if anything, an individual human being eschewing politics and money-making can do effectively on behalf of all humanity.”

Second, Fuller hoped to prevent others from profiting from his inventions. Donald W. Robertson served as Fuller’s patent attorney and wrote about his experience in The Mind’s Eye of Buckminster Fuller (Robertson, St. Martins 1983). Robertson described why Fuller sought patents: “While Fuller did not wish to seek patent profits by selling efforts, he was adamant in seeking to forestall efforts of others to profit by making unauthorized use of his inventions.” Fuller defended his patent interests. Fuller’s archive includes legal disputes over royalties with North American Aviation between 1958 and 1961 and with Ernest Okress between 1978 and 1979. According to Siobhan Roberts’ book on mathematician Donald Coxeter, King of Infinite Space (Roberts, Walker & Co. 2006), Fuller’s patent on the Radome was defended in Canada by the United States Department of Defense. Fuller sought and sometimes obtained intellectual property rights in Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Columbia, The Congo, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Finland, France, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United State, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Venezuela and West Germany.

All of Fuller’s inventions are lost in some way. All of Fuller’s U. S. patents are lost in that they have expired. Some of Fuller’s patents expired in his lifetime. This is due to his being unable to afford a renewal, or his deciding to let a patent expire, or perhaps neglect. Many of Fuller’s patents lost their references to earlier patents by other inventors. That is, what Fuller claimed he invented was in fact invented by someone else. Sometimes Fuller was ignorant of prior work, such as the octet-trus constructions of Alexander Graham Bell. Sometimes Fuller stole ideas whole-cloth, such Kenneth Snelson’s sculptures re-branded as Fuller’s tensegrity. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they have yet to go into production, existing only as scale models. Perhaps now that Fuller’s patents have expired some of them can be tested against Fuller’s claims. Perhaps the fog gun could be tested in arid environments, for instance. Many of Fuller’s patents are lost to the curious because they are not always filed under their popular name. The patent for the geodesic dome is to be found under the title ‘Building Construction,’ which has likely caused some researchers difficulty in finding it. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they are under-documented. Automobile restoration firm Crosthwaite and Gardiner had access to nearly all the information ever produced about the Dymaxion Car, but at times had to make their best guess in the creation of Dymaxion Car #4 because detailed schematics and photographs were not available. The credits to many of the illustrations in Inventions are lost. Illustrations appear in the book without further information. The photograph on the front cover is a 36-foot geodesic dome made by students at the University of Minnesota and assembled in Aspen, Colorado in 1952. Additional photographs of this dome can be found in Dymaxion World illustrations 334-339. The end papers show the paperboard dome of 1954. Page vi shows Fuller with a partially-assembled model of the 4D House in New York City in 1929. Page xi shows Fuller at Black Mountain College in 1948. Pages xvii and xviii appear to be Fuller at the Montreal World’s Fair dome. The photographs on pages xiv, xxvi-xxvii, xxxi and xxxii are of unknown origin.

The Dymaxion House / Wichita House is a house suspended from a central mast. The Dymaxion House / Wichita House of 1946 has no patent. In Inventions Fuller directs the readers to Grunch of Giants as to why the Dymaxion House did not go into production. Grunch of Giants claims this was due to a lack of a distribution system, difficulties with building codes, resistance from electricians and plumbers unions and an unwillingness by banks to offer mortgages. But there is no published explanation why Fuller or someone else did not patent the Dymaxion House. Grunch claims the Dymaxion House was designed in 1927, modeled in 1928 and helicopter-delivered in 1954. The Wichita House appears in Dymaxion World illustrations 184-227. Much of Fuller Houses by Federico Neder concerns the Dymaxion House. The most important information on why the Dymaxion House never went into production can be found on pages 85-114 of Martin Pawley’s Buckminster Fuller. Namely, this was due to Fuller’s “fanatical determination to retain complete personal control of the project and refine the house still further before putting it into production.” Although there were estimates of 250,000 Dymaxion Houses to be produced each year and 37,000 unsolicited orders before production began, not one complete full scale Dymaxion House was ever made. When the Henry Ford Museum attempted to restore the full size Dymaxion House, they learned that what is seen in photographs are two incompatible models, an interior and exterior. Only miniature models exist in complete form.

The Dymaxion House was one of Fuller’s best opportunities for financial success. Funding was available, materials and equipment was at hand, trained labor stood ready, but Fuller scuttled the entire operation. The challenges Fuller described in Grunch of Giants may have existed, but these challenges exist for every manufacturer and architect and designer who, nonetheless, are able to produce their work. Fortune magazine described the Dymaxion House as the industry that industry missed.

How the Dymaxion House was scuttled is underdocumented. The documentary Thinking Out Loud claims that the manufacturer was ready to proceed but Fuller objected, claiming the need for more testing. In Buckminster Fuller: An Autobiographical Monologue / Scenario (edited by Robert Snyder) Fuller speaks of the Dymaxion House being ready for mass production but says nothing about why this did not happen. J. Baldwin writes: “To prevent the marketing of an unperfected product, he ‘hid’ the engineering drawings by stamping them ‘obsolete.'” How Fuller was able to walk away with a design he did not own the intellectual property to is unknown.

But it could be that the Dymaxion House was simply not a viable product. Architect Philip Johnson had much to say about Fuller and the Dymaxion House in Thinking Out Loud, only a small amount of which was used. From the unaired transcript:

[The] Dymaxion House was probably the worst planned dwelling in the world. A round, small round space. Unless you’re an igloo, unless you like igloos and live like Eskimos in one room. But he believed in privacy, so he carved it up and made rooms at the beds. If you look at the plans today it is to laugh. The bed never got into the pie shape, pie shape room. There’s no way architecturally to make it work. But he tried anyhow. And he put an arched door in this mechanical looking thing.

And then he held it up in the central mast. Well if there’s one way not to hold up a house, it’s from the center. Frank Lloyd Wright tried the same thing you know. I mean it was in the air. It was in the air. A lot later it went into art through Snelson but in engineering it lasted for a long time. You hold down a building on the outside and hold it up in the middle. Well isn’t it easier, any common person would say, to hold it up all over? Why do you hold it all up and then pull it down again? Never made any sense. But ideologically it made wonderful sense. We have this central mast - you could see the poetry that would fit around a circular building around a mast. Perfect. Had nothing at all to do with architecture and all to do with dreams and pseudo mechanics.

Fuller describes an overhead-trolleyed, tensionally supported telephone in Dymaxion World. This appears to be a candlestick telephone hanging from a track that could be slid between desks in an office. Fuller never sought a patent for this telephone trolley.

Fuller describes a criss-cross, tensionally supported table in Dymaxion World. This appears to be a table supported by wires. Fuller never sought a patent for this table. Furniture suspended from above is as old as the first porch swing or folding table on a ship, but this particular suspended table is somewhat novel. Fuller never sought a patent for this tensionally supported table.

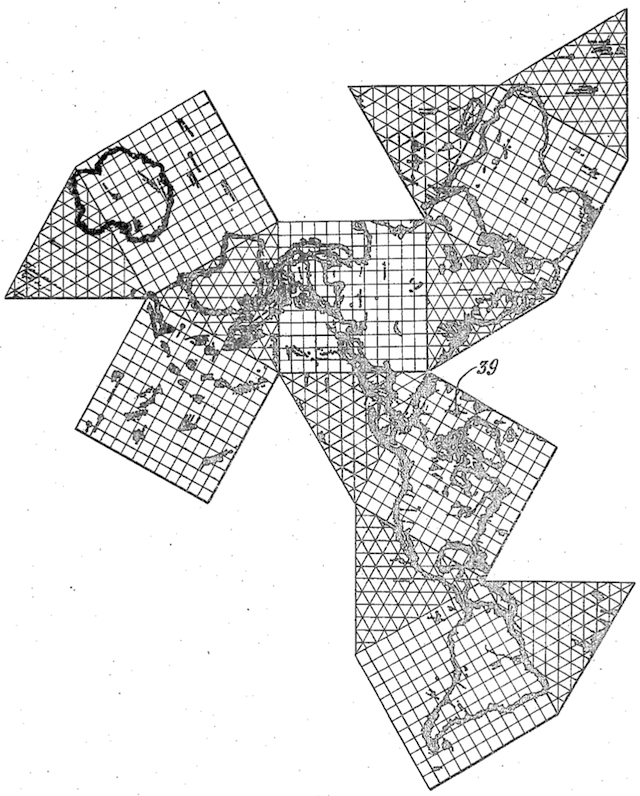

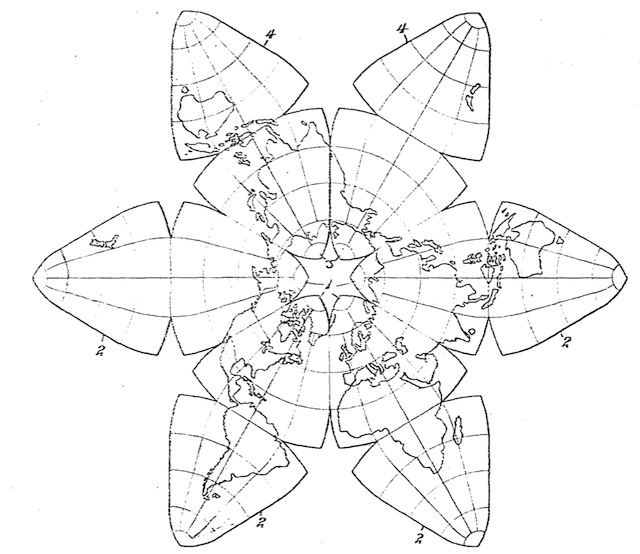

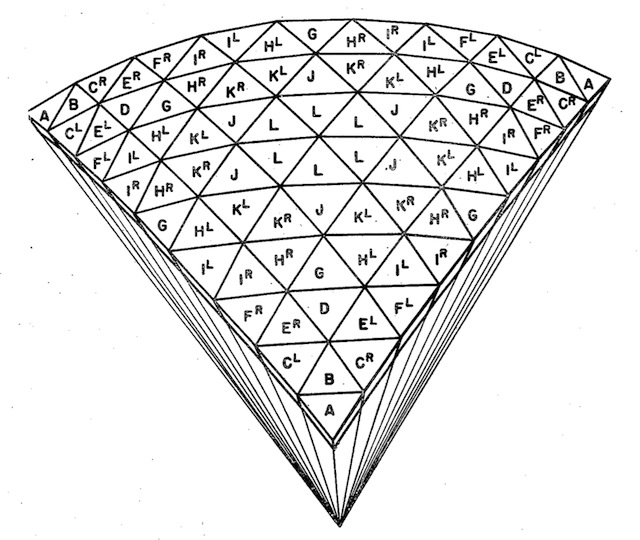

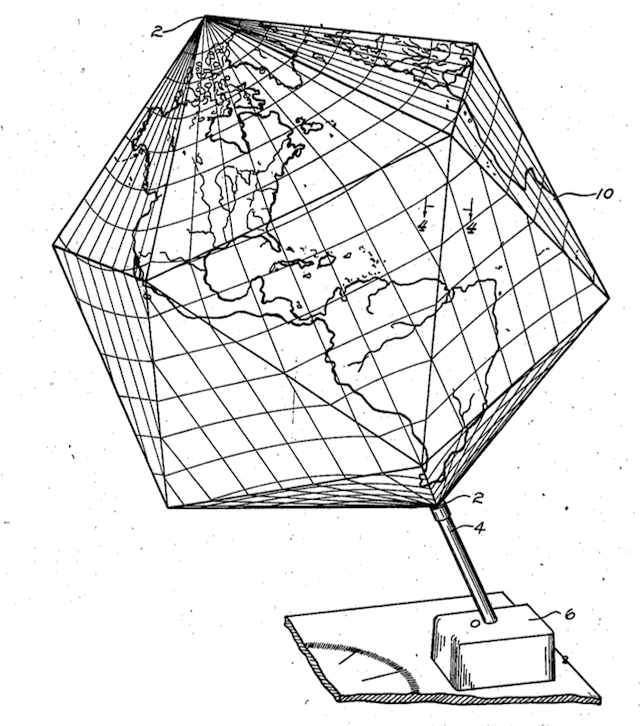

The Dymaxion Map is a map of the world. The Dymaxion Map is titled Cartography in patent 2,393,676 (29 January 1946). Grunch of Giants claims the Dymaxion Map was discovered in 1933 and published in 1943. Although Fuller wanted to employ an undistorted map in his efforts to coordinate people’s needs with existing resources, and although the Dymaxion Map is a worthy addition to the history of cartography, it is not a map free of distortion. All flat maps of curved surfaces are distorted. The Dymaxion Map distorts in a novel way, but it still distorts. Fuller claims that after the Dymaxion Map appeared in Life magazine it was described as “pure invention” by “several great experts.” This description was used by Fuller’s patent attorney to convince the Patent Office Fuller’s work deserved a patent. Fuller’s “pure invention” claim does not appear in Robertson’s The Mind’s Eye. Robertson quotes Fuller saying “The problem of the navigator is how to sail or fly the shortest course, which on a conventional chart will be a curved line. I simply design an unconventional chart which is so constructed that all future navigators can find their courses as straight lines. This means that I will need a new kind of map projection in which all great circles of a sphere will be seen as straight lines.” Fuller claimed that his 1947 world map patent was the first to be granted since 1900, when the U. S. Patent office ruled all possible methods had been considered. But Allan C. Clark had been granted patent 2,369,103 in February 1945 for “flat map sections which may be detachably assembled upon a support to form globe maps.” And on 12 December 1924 Samuel W. Balch had been grated patent 1,610,413 for a map with the following features:

For the purposes of navigation it is important to have maps or charts on flat or plane sheets which fulfill three mathematical conditions. First, the construction should be such that it will be convenient to draw on the map the course of the shortest sea-level line between any two points, and to ascertain the latitude and longitude at any intermediate point of the course. Such a line is commonly known as the arc of a great circle and would be if the earth were a true sphere but is in, fact a line to be otherwise defined since the earth approximates closely to a spheroid or ellipsoid of revolution, and will be termed a geodesic line. Second, it should be convenient to ascertain the angle at which any geodesic line crosses any intermediate meridian.

Gene Keyes has documented the work of B. J. S. Cahill and Cahill’s Butterfly World Map. The Butterfly World Map is a globe flattened into eight symmetrical rounded triangles in which the sinus lines do not cut through large land masses and distortion of land masses is kept at a minimum. These are claims make by Fuller for his Dymaxion Map, but the Butterfly World Map was introduced in 1909. Cahill spoke of his Butterfly World Map in 1912:

The ideal way to study the world is by use of a globe, and all geographers are agreed on this point, it follows that a map which is identical with the surface of a globe, laid out literally on a plane, must be the best as being nearest to an actual globe. […] I will go further and say that a map so made has advantages that a globe has not. One of them is that the map shows the entire world at one coup d’il, whereas on a large globe one can only see about a third of the earth’s surface at one time.

The patent specifies that the Dymaxion Map is “resolved into six equilateral square sections and eight equilateral triangular sections.” This does not describe the icosohedral Dymaxion Map (known as the Raleigh projection) that is often associated with patent 2,393,676. Inventions mentions the Dymaxion Map in Life magazine, but not one of the ways in which this “flat map shows [the] world in many perspectives.” This was the “Jap Empire.” “The ruthless logic of the Jap imperialism is exposed by this layout of the Dymaxion World map. The “Jap Empire” was not included in the reprint from Life found in Dymaxion World page 153.

The Dymaxion Map is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them.

The Jitterbug Transformation appears in Fuller’s work starting in 1948, as part of his study of the closest packing of spheres.

What Fuller discovered was that a wire-frame cuboctahedron with flexible vertices has the property of flexing into other shapes. If the upper and lower triangular face are pushed toward each other, the cuboctahedron forms a shape similar to the icosahedron (although missing some edges). If the upper and lower triangles are pushed further toward each other, the cuboctahedron forms an octahedron. A flexible cuboctahedron can be manipulated further to form a tetrahedron and a triangle. These transformations were entirely the discovery of Buckminster Fuller.

The Autonomous Package is a collection all the furniture and utilities needed by a family of six packed into a single container. The Autonomous Package was developed by Fuller and students at the Dearborn Street Institute of Design in Chicago, Illinois in 1948. This project predicted the utility of intermodal containers, standardized containers that can be filled and delivered by air, sea and land without being repackaged. This project also predicted the popularity of stores like Ikea, which sells collections of furniture and utilities in ready-to-assemble form.

Fuller never attempted to patent the Autonomous Package. In Dymaxion World he write that the Autonomous Package was “not significant in its superficial results.” The Autonomous Package is a case of Fuller demonstrating the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of a technique then moving on, with the world adopting his discovery while not knowing its origin.

Dymaxion patent Fastening Means 2,466,013 (5 April 1949) is not mentioned in Inventions, Dymaxion World or in any other Fuller title. Fastening Means (2,466,013) was filed by Bill Dean Eaton. Fastening Means reads: “This invention particularly relates to fastenings of the blind rivet type comprising a malleable metal tubular stud having an outside flange at one end and with its inside provided with a screw thread with the thread starting at a position spaced from the flanged end and extending toward the opposite end of the stud this latter end being either open or closed.”

While not limited to use on a Dymaxion Dwelling Unit, this patent was assigned to the Dymaxion Company. In some cases Fuller was able to give partial credit to prior inventions, or to share the stage with other inventors. James Monroe Hewitt’s patent 1,633,702 for Building Structure (28 June 1927) appears in both the Chronofile and Inventions. Hewitt’s earlier patent 1,631,373 for Partition Walls (7 June 1927) appears in the Chronofile but not in Inventions. The Tensegrity Trus of Christopher J. Kitrick appears in Inventions. But the Dymaxion patent for Fastening Means is lost in the Fuller literature.

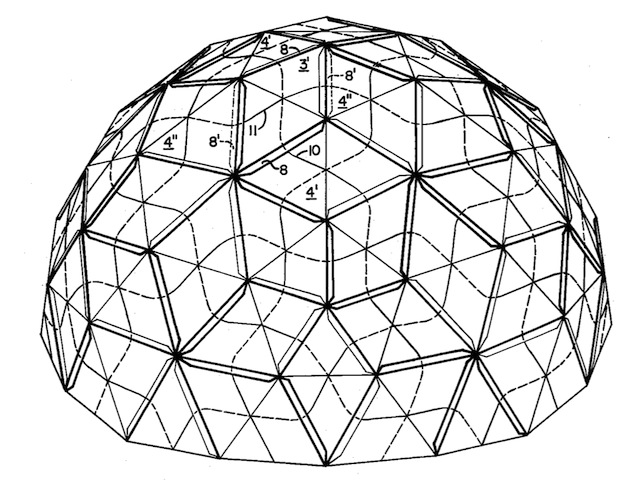

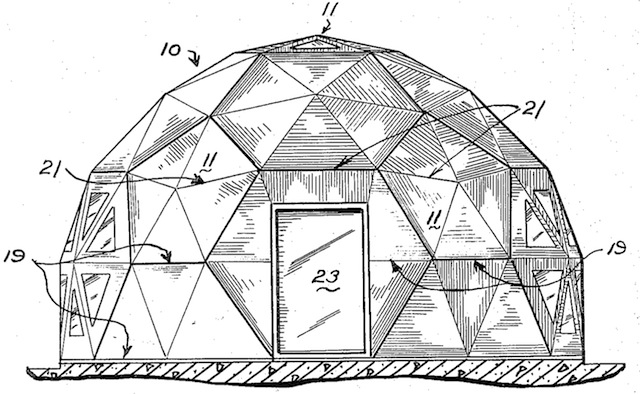

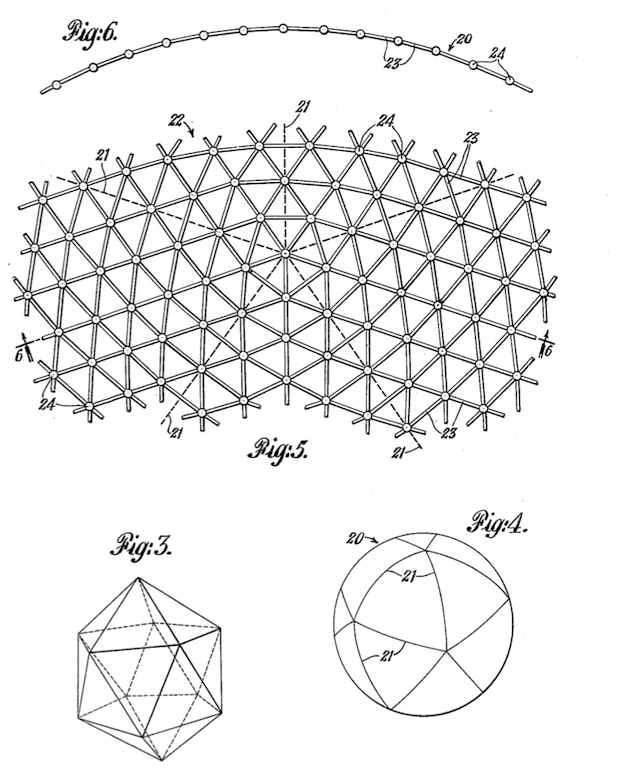

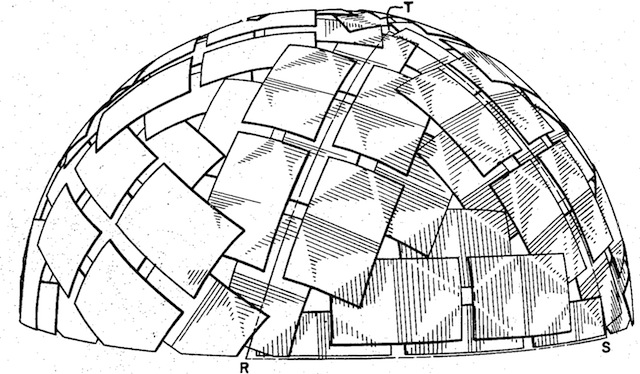

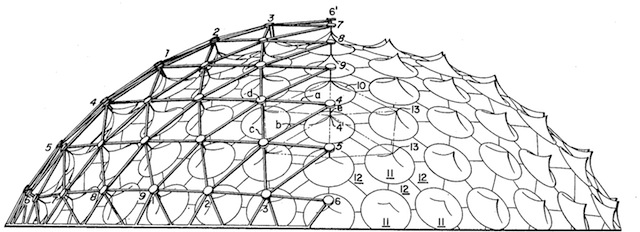

The Geodesic Dome is a shelter shaped like an inverted bowl. The Geodesic Dome is called Building Construction in patent 2,682,235 (29 June 1954). The photograph on page 128 was taken inside the Climatron in St. Louis, Missouri USA. The photograph on page 138-139 was taken outside the U. S. Pavilion at the Montreal World’s Fair. It is unknown where the photographs on pages 132, 1134-135 were taken. Fuller’s U. S. patent was granted on 29 June 1954, his Canadian patent in 1955, but this is not the first patent for a geodesic dome.

The first patent for a geodesic dome was awarded to Walter Bauersfeld (1879-1959) in 1925. Bauersfeld’s patent is Reichspatentamt Patentschrift Nr. 415395 Klasse 37a Gruppe 2. A U. S. patent preceding Fuller’s geodesic dome is Insulation for Spherical Tank Shells and Methods for Making the Same (2,470,986), granted to J. O. Jackson on 24 May 1947. Jackson’s patent describes the faces of an icosahedron divided into any number of triangles, the projection of the vertices of these triangles outward until they intersect with the surface of a sphere, then connecting the points of intersection with radial lines forming the chords of great circles. The resulting “dome-like” structure is described as “less troublesome, costly, and wasteful” as conventional structures.  Jackson’s patent, in turn, makes reference to patent 2,424,601 - Icosahedral Map by J. E. Crouch, granted on 29 July 1947.

Jackson’s patent, in turn, makes reference to patent 2,424,601 - Icosahedral Map by J. E. Crouch, granted on 29 July 1947.

The Geodesic Dome is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them at the time of his patent.

The Paperboard Dome is a kind of Geodesic Dome, made of folded cardboard tubes and panels. The Paperboard Dome is called Building Construction in patent 2,881,717 (14 April 1959). Canadian patents were awarded the same year. The photograph on page 146 features the 1954 Mark II dome, which can be seen in illustrations 426-433 of Dymaxion World (see also Military Domes). The twenty-foot paperboard dome and the Lower East Side gang that built it mentioned by Fuller is described at length in CHARAS by Syeus Mottel.

The Paperboard Dome, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. But the use of what is now known as cardboard in this folded form is unique to Fuller.

The Plydome is a kind of Geodesic Dome, made of overlapping sheets of plywood. The Plydome is called Self-Strutted Geodesic Plydome in patent 2,905,113 (22 September 1959). Dymaxion World illustrations 435-442 show other plydomes. The Geodesic Plydome chapel of Colombian Fathers in illustration 447 was built in 1957, the year Canadian patents for the Plydome were awarded to Fuller.

The PlyDome, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. But while shingling is an old architectural form, shingles-as-roof-and-walls is a form unique to Fuller.

The Catenary (Geodesic Tent) is a kind of Geodesic Dome, made of a tent suspended from a metal geodesic frame at multiple points. The Catenary Dome is called called Geodesic Tent in patent 2,914,074 (24 November 1959). The Alaskan dome mentioned by Fuller was built by Synergetics Inc. of Raleigh NC USA in 1956. The 100-foot diameter dome was erected, disassembled, shipped and re-assembled in Afghanistan, Algeria, El Salvador (twice), France, Osaka (Japan), Peru, Syria, Thailand, Tokyo (Japan) and Uruguay before its use in the 1967 Alaskan Centennial. This was one of the most field-tested domes ever made and there is no record of it having given sub-standard performance. One wonders what the town of Fairbanks did with the dome after it was disassembled. The second Dymaxion Car vanished for decades. Perhaps the Alaska dome will likewise make a dramatic reappearance.

The Cantenary Geodesic Tent, as a dome, is preceded by similar inventions. But the application of circus-tent like structures to the dome’s facets is a form unique to Fuller. Millions of modern camping tents, with their dome shape supported by tension members, owe their existence to Fuller’s Cantenary Geodesic Tent.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller (Part 1 of 3)

The Lost Inventions of R. Buckminster Fuller is a three-part investigation into the inventions of Buckminster Fuller. These essays can serve as companion essays for two previous books by and about Fuller: Inventions (Fuller, St. Martin’s Press 1983) and The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (Marks and Fuller, Doubleday 1973). Ownership of these two books is not necessary for reading these essays. Page numbers without citations are from Inventions Fuller made many claims about his inventions, claims which are confirmed or called into question by these essays. A new appreciation for Fuller’s innovations is the result.

Fuller claimed that his life goal was to provide humanity with the means to save itself from itself and from natural disasters. To that end Fuller could have given his inventions up to the public domain, making them more accessible to more people. But Fuller sought, obtained and defended patents for many of his inventions, for two reasons.

First, Fuller hoped that the long-term and public nature of the US Patent Office would serve as a long-term and public record of his work. Fuller wrote in Inventions: “The public record established by my patents […] can serve as a critical appraisal of the historical relevance, practicality, and relative effectiveness of my half-century’s experimental commitment to discover what, if anything, an individual human being eschewing politics and money-making can do effectively on behalf of all humanity.”

Second, Fuller hoped to prevent others from profiting from his inventions. Donald W. Robertson served as Fuller’s patent attorney and wrote about his experience in The Mind’s Eye of Buckminster Fuller (Robertson, St. Martins 1983). Robertson described why Fuller sought patents: “While Fuller did not wish to seek patent profits by selling efforts, he was adamant in seeking to forestall efforts of others to profit by making unauthorized use of his inventions.” Fuller defended his patent interests. Fuller’s archive includes legal disputes over royalties with North American Aviation between 1958 and 1961 and with Ernest Okress between 1978 and 1979. According to Siobhan Roberts’ book on mathematician Donald Coxeter, King of Infinite Space (Roberts, Walker & Co. 2006), Fuller’s patent on the Radome was defended in Canada by the United States Department of Defense. Fuller sought and sometimes obtained intellectual property rights in Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Columbia, The Congo, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Finland, France, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United State, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Venezuela and West Germany.

All of Fuller’s inventions are lost in some way. All of Fuller’s U. S. patents are lost in that they have expired. Some of Fuller’s patents expired in his lifetime. This is due to his being unable to afford a renewal, or his deciding to let a patent expire, or perhaps neglect. Many of Fuller’s patents lost their references to earlier patents by other inventors. That is, what Fuller claimed he invented was in fact invented by someone else. Sometimes Fuller was ignorant of prior work, such as the octet-trus constructions of Alexander Graham Bell. Sometimes Fuller stole ideas whole-cloth, such Kenneth Snelson’s sculptures re-branded as Fuller’s tensegrity. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they have yet to go into production, existing only as scale models. Perhaps now that Fuller’s patents have expired some of them can be tested against Fuller’s claims. Perhaps the fog gun could be tested in arid environments, for instance. Many of Fuller’s patents are lost to the curious because they are not always filed under their popular name. The patent for the geodesic dome is to be found under the title ‘Building Construction,’ which has likely caused some researchers difficulty in finding it. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they are under-documented. Automobile restoration firm Crosthwaite and Gardiner had access to nearly all the information ever produced about the Dymaxion Car, but at times had to make their best guess in the creation of Dymaxion Car #4 because detailed schematics and photographs were not available. The credits to many of the illustrations in Inventions are lost. Illustrations appear in the book without further information. The photograph on the front cover is a 36-foot geodesic dome made by students at the University of Minnesota and assembled in Aspen, Colorado in 1952. Additional photographs of this dome can be found in Dymaxion World illustrations 334-339. The end papers show the paperboard dome of 1954. Page vi shows Fuller with a partially-assembled model of the 4D House in New York City in 1929. Page xi shows Fuller at Black Mountain College in 1948. Pages xvii and xviii appear to be Fuller at the Montreal World’s Fair dome. The photographs on pages xiv, xxvi-xxvii, xxxi and xxxii are of unknown origin.

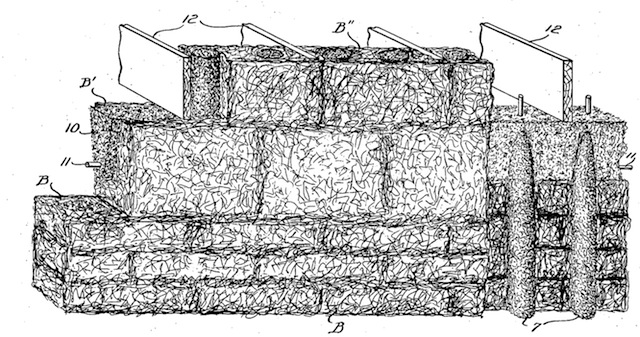

The Stockade Building Structure is a method of making bricks that have holes in them, and the method of sliding those holes over standing metal poles (a ‘stockade’). The Stockade Building Structure is called Building Structure in patent 1,633,702 (28 June 1927). It is patented by James Monroe Hewitt and Fuller. The Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process is called Mold for Building Blocks and Process of Molding in patent 1,634,900 (5 July 1927), awarded to Fuller. Fuller was the President of Stockade Building System Inc., according to Buckminster Fuller’s Universe by Lloyd Sieden. Becoming Bucky Fuller by Loretta Lorance offers the most complete account so far of Fuller’s complex relation to Stockade. In brief, Fuller’s father-in-law Hewitt gave Fuller a hand in the company in hopes Fuller could turn from drinking to supporting his daughter, Anne Hewitt. A companion photograph to the one on pages 2 and 3 of Inventions can be found on page 34 of Buckminster Fuller: An Autobiographical Monologue / Scenario by Fuller’s son-in-law Robert Snyder and illustration 9 from Dymaxion World. Fuller writes in Inventions that this process was invented by his father-in-law, Monroe Hewlett. This is confirmed by Hewlett’s earlier patents 1,604,097 (19 October 1926) and 1,450,724 (3 April 1923). Neither of these earlier patents appear in Inventions. Dymaxion World claims the Stockade System was “co-invented” by Fuller and Hewitt. Fuller writes in Inventions that “while I did much of the inventing of technologies, the [Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process] was the only one I felt was worth patenting.”

The Stockade Building Structure was co-invented by Fuller. The Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process was invented and patented by Fuller.

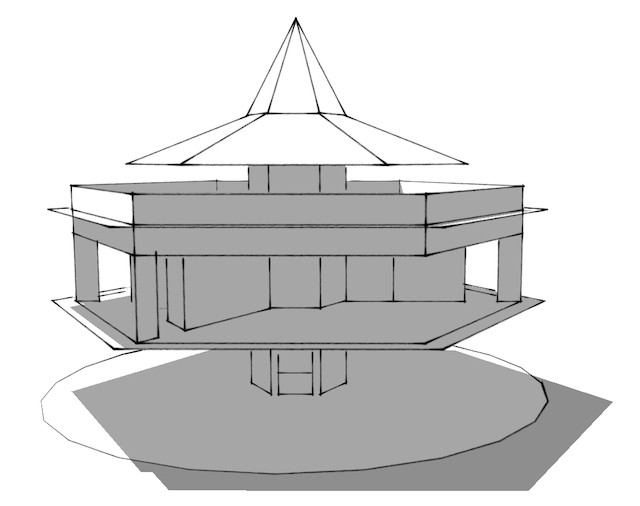

The 4D House is a house which, instead of resting on the ground, is suspended from a central mast. The 4D House has no patent. Inventions claims the patent was submitted in 1928, rejected, and Fuller did not re-submit out of ignorance that this was an option. Fuller does not state why he did not re-submit when he learned that this was an option. Inventions also claims the 4D House patent is rectilinear like a conventional house because his unnamed patent attorney advised him it would be more convincing to the patent examiners. The illustrations of the 4D House in Inventions are generally of a hexagonal building rather than the rectilinear building in the patent itself. Dymaxion World calls the hexagonal 4D House the “clean-up model” in illustration 40 and is seen in illustrations 40-41 and 49-64. Variations of the hexagonal 4D House are seen in Dymaxion World illustrations 2, 16-39 and 66.

In Buckminster Fuller’s Universe, Sieden writes that Fuller offered the rights to the 4D House to the American Institute of Architects as a gift and that this gift was rejected. According to Becoming Buckminster Fuller, Fuller was not ignorant of the patent process because he did pursue it before, at the time and afterwards. The patent for the 4D House was abandoned because of the 43 claims made in his application, all 43 could be found in earlier patents. Attorney D. H. Sweet is blamed for the rectilinear 4D House in his patent application but Fuller’s own sketches to this point had been rectilinear.

The 4D House is preceded by similar inventions.

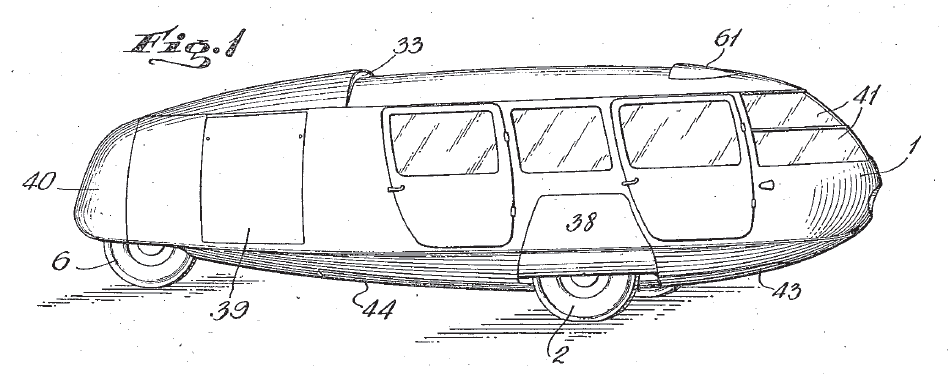

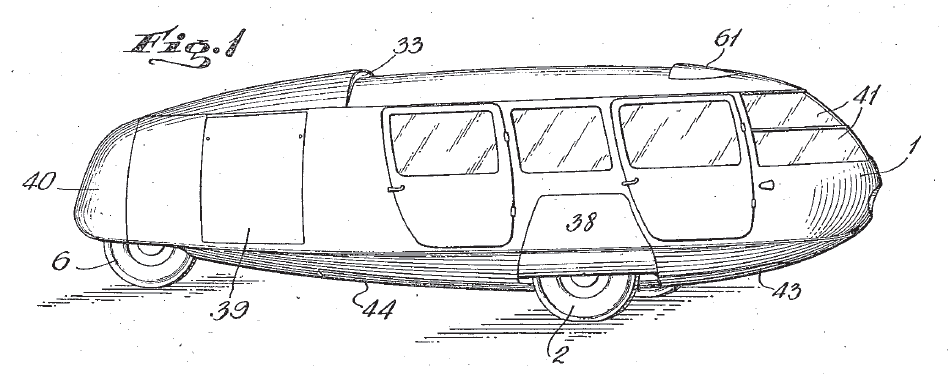

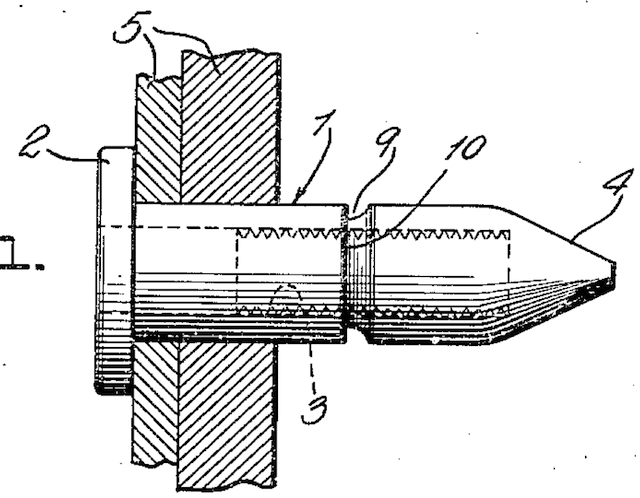

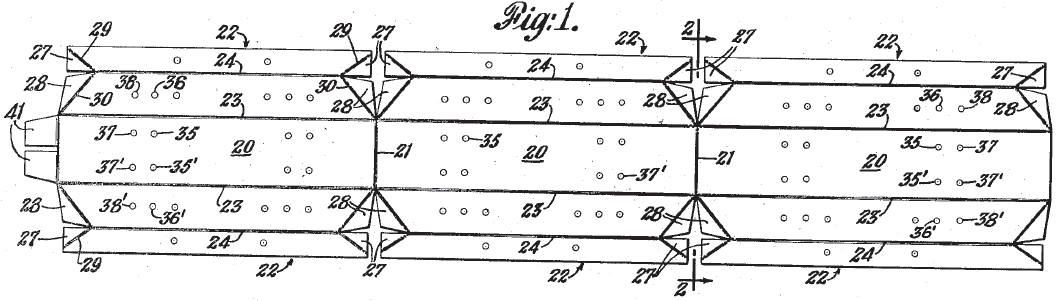

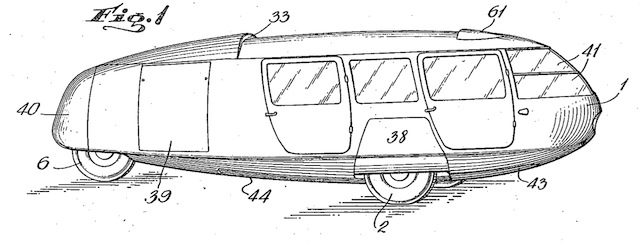

The Dymaxion Car is a three-wheeled automobile. The Dymaxion Car is called a Motor Vehicle in patent 2,101,057 (7 December 1937). The patent was assigned to Buckminster Fuller. Inventions includes the Great Britain patent for the Dymaxion Car. Fuller was the Director and Chief Engineer of the Dymaxion Corporation. The patent drawings most closely resemble Dymaxion Car #1, but two different Dymaxion Cars were produced and two more yet were conceived. In 2010, automobile restoration company Crosthwaite and Gardiner produced Dymaxion Car #4, based primarily on Dymaxion Car #2.

The photograph on pages 32-33 of Inventions shows Dymaxion Car #1 outside the Dynamometer Building of the Locomobile plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Locomobile produced cars from 1899 to 1929. This is the building that produced the first three Dymaxion Cars. The building was leased by W. Starling Burgess. Burgess produced a yacht in the building while contributing to the creation of the Dymaxion Car. The automobile in the upper left corner is a Franklin. Artist Diego Rivera is seen between the car doors with his jacket in his arms.

The earliest newspaper and magazine articles on the subject tend to favor W. Starling Burgess as the main force behind the Car. The Dymaxion Car is first mentioned in print in the New York Times on 1 June 1933. It is described as the creation of W. S. Burgess. The last sentence of the article reads: “Buckminster Fuller, New York architect and engineer, is associated with Mr. Burgess in the project.” By 22 July the New York Times comes to describe Fuller as the inventor of the Dymaxion Car and Burgess as the designer. The magazine Modern Mechanix of October 1933 lists Burgess and Fuller as co-designers of the Car. On 22 October the New York Times described the vehicle as the “streamlined, three-wheeled Gulf-Dymaxion Car, designed by W. Starling Burgess and Buckminster Fuller.” At the time, Gulf Oil had purchased advertising space on the side of the Car. Dymaxion World describes Burgess as “an assistant” in the project.

The Morgan Motor Company had been producing three-wheeled vehicles in the USA since 1909. The Burney, produced by Streamline Cars, used aviation design principles as early as 1927. The Chrysler Airflow was a streamline, drag-reducing car of 1934, as was the Tatra T77 of 1935.

The Dymaxion Car is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them. The public record initially credits Burgess as the inventor of the car, then credits Burgess as a co-inventor with Fuller, then Fuller in the lead with Burgess as an assistant, and finally Fuller alone.

Fuller seems to have had some role in the development of disc brakes during his employment at Phelps Dodge in 1937. Buckminster Fuller’s Universe describes Fuller’s invention as “a revolutionary solid bronze drum fitted with rubber insets to dissipate heat very rapidly, thereby solving [problems] which had plagued automobile and truck breaking systems for decades.” His new breaks also cut stopping times by nearly 50 percent and were the forerunner of the now-popular disc breaks. Grunch of Giants describes this invention as “carbon blocks-inserted, copper disc-brakes” that were “successfully demonstrated” in 1937. BuckyWorks claims that Fuller had considered disc brakes for the second Dymaxion Car (circa 1934). Fuller’s contribution to disc brakes is underdocumented.

Another 1937 Phelps Dodge invention of Fuller was a bunsen-burner-melted, water-cooled centrifuge for processing low-grade tin ore. This is mentioned in Grunch of Giants but does not appear in Inventions or Dymaxion World. What this invention might be and its impact on the world has yet to be documented.

The Fog Gun is a misting showerhead. The Fog Gun appears in Dymaxion World illustration 88-92 but not in Inventions. Grunch of Giants claims the Fog Gun was designed in 1927 and prototyped in 1949. Dymaxion World, Buckminster Fuller’s Universe and other sources quote Fuller claiming that while in the Navy he was able to clean grease off his hands by the mist eternally surrounding ships at sea. The fog gun is mentioned in Fuller’s 1938 book Nine Chains to the Moon. The fog gun was a means of directing atomized water under pressure for hygiene purposes. Dymaxion World claims the fog gun was tested at the Institute of Design in Chicago in 1948 “and subsequently at Yale and other universities.” In these tests a one-hour “massaging pressure bath” used one pint (.47 liters) of water. In session 11 part 2 of Fuller’s 42-hour lecture “Everything I Know,” Fuller claims professional dermatologists were consulted in researching the fog gun. Dymaxion World continues by saying “If fog gun bathing were done in front of a heat lamp, [all the effects of bathing] could be effected without the use of any bathroom. Since there would be no run-off waters, tons of plumbing and enclosing walls could be eliminated, and bathing would become as much an ‘in-the-bedroom’ process as dressing.” Buckminster Fuller’s Universe claims the test of the fog gun found it to be “a completely satisfactory system of cleansing, which, in fact, caused less damage to skin than ordinary soap and water. Thus, another significant artifact was created and left until a time when future generations would require it.” There is no record of Fuller seeking a patent for the Fog Gun.

The James Dyson Award is an international student design award with the challenge to “design something that solves a problem.” An uncredited Malaysian entry in 2011 describing a Mist Washer reads:

A mist nozzle inside the basin can produce mist which is mixture of water and soap to wet our hand. Later, water nozzle will spray water with medium velocity to clean our hand. […] High velocity water can helps in cleaning our hands, like the high pressure jet that we use in industrial for cleaning purpose, but in a small scale and lower pressure. […] Compare to common water tap, it is more clean and convenient because the user will never contact to the tap which had a lot of bacteria. […] There are only 1% of water is clean, it will be a serious issue in the future about the usage of water. So, this mist washer can reduce the usage of water to minimum because of the high pressure water nozzle. Compare to common water tap, mist washer is more environmental friendly.

Fuller’s Fog Gun is an invention whose generation may have arrived.

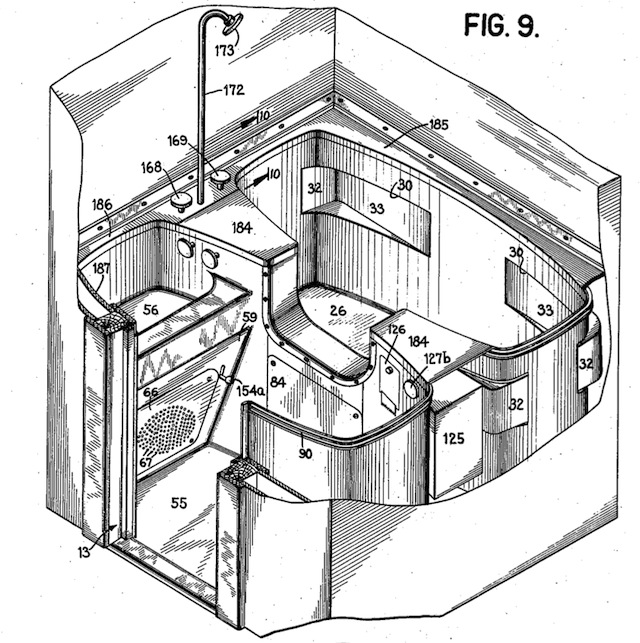

The Dymaxion Bathroom is a metal one-piece bathtub, sink and toilet. The Dymaxion Bathroom is called a Prefabricated Bathroom in patent 2,220,482 (5 November 1940). Grunch of Giants claims the Dymaxion Bathroom was designed in 1928, prototyped in 1936 and “mass-produced in polyester fiberglass in West Germany, 1970.” In 1936, Phelps Dodge wanted to expand their operations from mining copper to manufacturing copper products. Fuller was hired by Phelps Dodge as a director of research and allowed to pursue any area of interest he chose. Among his work for Phelps Dodge was the Dymaxion Bathroom. Earlier patents for a prefabricated bathroom include Orville Smith’s 2,131,124 (30 October 1938), Samuel Samelow’s 2,087,121 (13 July 1937), Ralph Otwell’s 1,931,392 (17 October 1933), Owen Ayer’s 1,763,209 (10 June 1930) and others.

The Dymaxion Bathroom is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them. In Dymaxion World, Fuller claims that the use of red and blue handles to indicate hot and cold running water comes from the Dymaxion Bathroom. Fuller did not claim to invent chemical toilets but he did suggest that the Dymaxion Bathroom could package waste to be picked up with other household waste and re-used by industry. This suggestion precedes the popularity of curbside recycling by decades.

The Mechanical Wing was a trailer-drawn mobile home, described in the October 1940 issue of The Architectural Forum. The Mechanical Wing included Fuller’s Dymaxion Bathroom and Fog Gun as well as the usual amenities of a mobile home. In Dymaxion World Fuller emphasizes that his invention was the cylindrical metal A-frame trailer of the Mechanical Wing, an invention later “popular as a trailer frame for transporting boats.” A similar A-frame trailer had been patented by P. L. Melanson in 1930 as Trailer for Vehicles (1,779,887).

The Mechanical Wing is preceded by a similar invention, but there is no indication Fuller was aware of it.

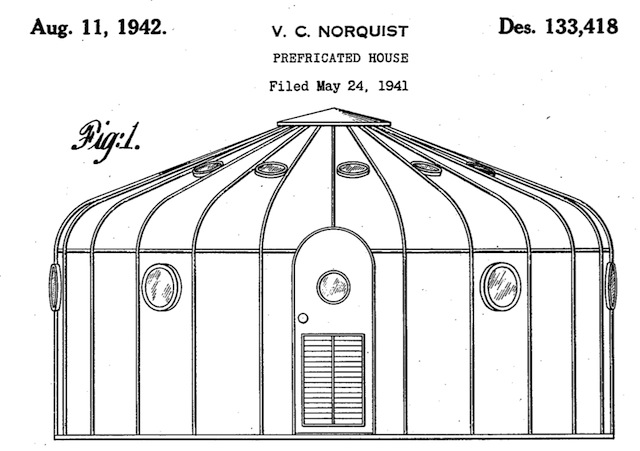

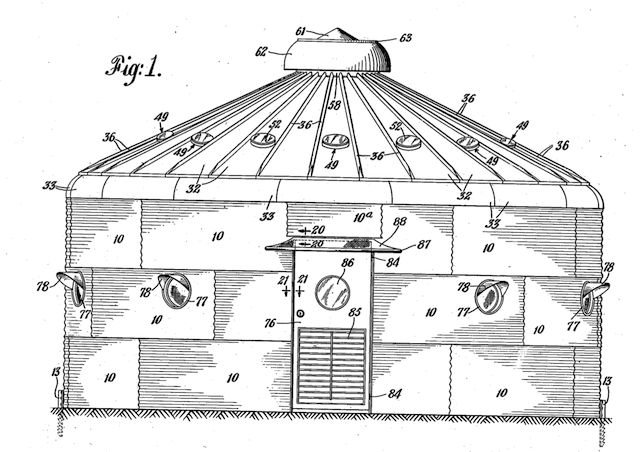

The Dymaxion Deployment Unit is a grain bin repurposed as a human shelter. The Dymaxion Deployment Unit (sheet) is called a Building Construction in patent 2,343,764 (7 March 1944). The Dymaxion Deployment Unit (frame) is called a Building Construction in patent 2,351,419 (13 June 1944). Fuller was the Director and Chief Engineer of the Dymaxion Corporation. Dymaxion World illustration 167 identifies the photograph on pages 54-55 of Inventions as having been taken in Haynes Point Park, Washington DC in April 1941. The photograph on page 61 of Inventions appears again with an exterior shot in Dymaxion World images 163 and 164. The photograph on page 68 includes Walter Sanders (head of the Department of Architecture at the University of Michigan) and his wife. The couple lived in the DDU for an unspecified period of time according to Dymaxion World. Dymaxion World emphasizes that Fuller modified the roof of an existing grain bin, giving it a more curved surface. This modification appears to be the basis for Fuller’s claim to inventing the Dymaxion Deployment Unit.

Two patents related to the Dymaxion Deployment Unit have a questionable history. Fuller’s Design for a Prefabricated House 133,411 does not appearing in Inventions. This patent is a near-identical copy of Design for a Prefabricated House 133,418 filed by Victor C. Norquist. Norquist had dozens of patents to his credit. Many of Norquist’s patents were assigned to Butler Manufacturing, which produced the Dymaxion Deployment Units. Norquist’s patent reads: “Be it known that I, Victor C. Norquist […] have invented a new, original and ornamental Design for a Prefabricated House of which the following is a specification… ” Fuller’s patent reads: “Be it known that I, Richard Buckminster Fuller […] have invented a new, original and ornamental Design for a Prefabricated House of which the following is a specification… ” The texts of 133,418 (Norquist) and 133,411 (Fuller) are nearly identical and the illustrations are nearly identical. Both patents are awarded on the same day, 11 August 1942. Norquist filed on 24 May 1941 and Fuller filed a week later on 31 May 1941. Norquist’s patent was awarded two years before either of Fuller’s Dymaxion Deployment Unit patents appearing in Inventions.

The Dymaxion Deployment Unit is preceded by similar inventions. Fuller’s patent is a copy of Norquist’s patent.