Buckminster Fuller and the Homeless of New York

If Buckminster Fuller is known for any effort, it is the effort to provide shelter. But who did Fuller actually provide shelter for? The Lightful House and 4D House existed only on paper. The Dymaxion House existed only as a small scale model. The Dymaxion / Wichita House existed as two full-scale models (one internal, one external, neither able to be connected to the other). The Dymaxion Deployment Unit did house a small number of US armed forces personnel but the DDU was the invention of Victor C. Norquist, not Buckminster Fuller. The geodesic dome was invented by Walter Bauersfeld. Of the dozens of books by and about Fuller, of the thousands of articles on his life and work, most of them fail to give a single instance of when Fuller actually provided shelter to anyone. The Buckminster Fuller Bibliography by Trevor Blake is the first book to document that Fuller provided shelter for others with his own direct effort.

The New York Times for 10 September 1932 includes an uncredited article titled “Single Jobless Men to Get Lodging House / Social Worker and Engineer Obtain Use of Tenement for Those Ineligible for City Aid.” The building in question was a then-deserted seven-story building located at 145 Ridge Street in New York City, New York. The social worker was Ben Howe and the engineer was Buckminster Fuller. Fuller is described as “editor of the magazine Shelter and head of Structural Study Associates, an engineering firm.” According to the article, the men who were renovating the building were hoping to live in it afterward. They were otherwise ineligible for benefits because they were not the head of a family. The building was to house two hundred and fifty men at a time and serve several thousand during Winter. Lieutenant R. E. Johnson was also involved in this project. He is described as a “former army construction engineer and commander of the United States Ex-Service Men’s Association.” At the time of the article, the shelter was under construction. The building described in this article no longer exists.

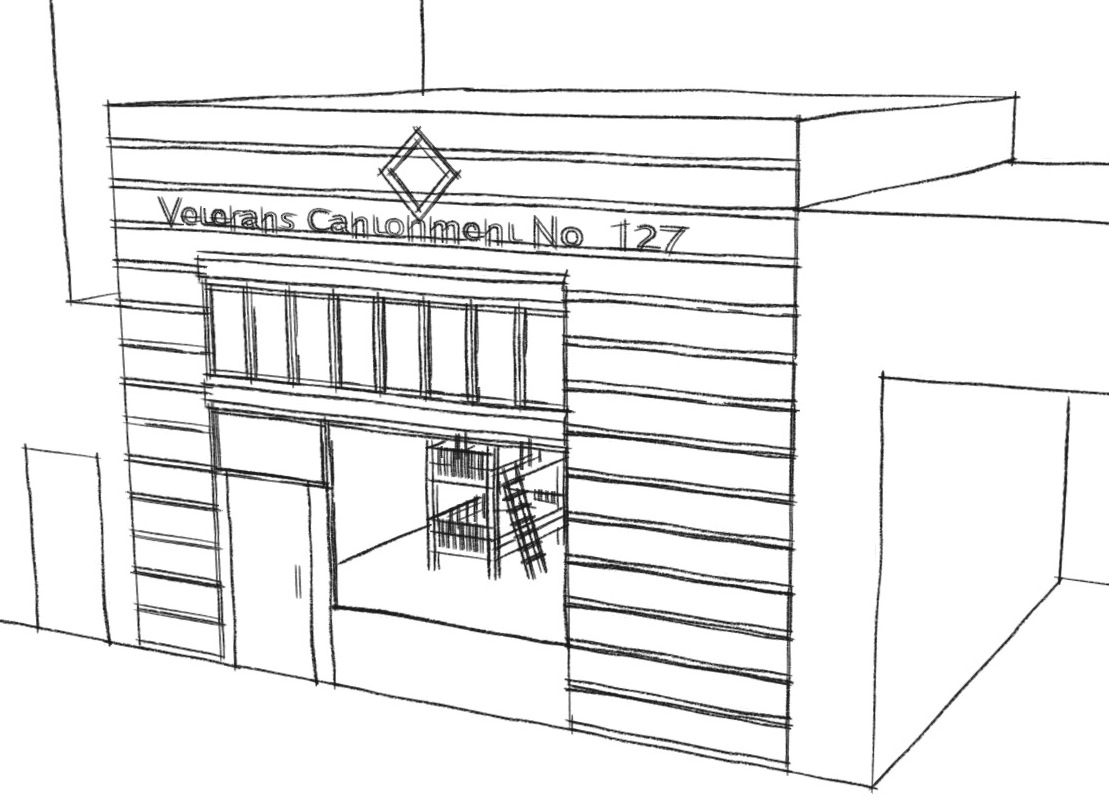

The New York Times for 2 December 1932 includes an uncredited article titled “Jobless Veterans Back in Barracks / 300 Single Men to Live Under Military Rule in Converted Clubhouse in 54th St.” The building in question was a five-story converted boy’s club at 340 East 54th Street in New York City, New York. According to the article, the shelter would be run by and for veterans and in a military style. The shelter would serve single men because of their difficulties in obtaining relief from existing services. The plan was initiated by a meeting of representatives of various interested organizations at the office of Raymond V. Ingersoll. Ingersoll served as a New York Parks Commissioner and as a Brooklyn Borough President. A residential development named after Ingersoll stands today at 120 Navy Walk in Brooklyn, New York. The representatives at the meeting included Ben Howe and Buckminster Fuller of the 145 Ridge Street shelter, Philip Hiss, Colonel Walter L. DeLamater, Arthur Huck, Louis Gleich, Owen R. Lovejoy, Cyrus C. Perry, James R. Sichel and Henry C. Wright. Philip Hiss went on to design and build homes in Florida, although he was not a trained architect. Col. DeLamater served in the 71st Infantry Regiment, an organization of the New York State Guard. Arthur Huck worked on numerous homeless shelter projects in the New York area, as reported in decades of articles found in the New York Times. Louis Gleich was a commander in the New York County Council of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and was the chairman of the committee that erected a VFW monument in Union Square. Owen Lovejoy served as the General Secretary of the National Child Labor Committee. The building formerly housed the Kips Bay Boys’ Club, where Lovejoy served as secretary. The building was to be called Veterans Cantonment No. 1. At the time of the article, the shelter was in operation. The building described in this article may still exist, next to the building that currently is designated as 340 East 54th Street.

By 1932, Buckminster Fuller had published drawings of his 4D House and exhibited models of his Dymaxion House. He had been featured in the Chicago Evening Post, Fortune Magazine, the Harvard Crimson, Modern Mechanics Magazine, the New York Times and Time Magazine. Fuller had published his monograph 4D and was publishing Shelter Magazine. He had earned the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade in the United States Navy. In 1933 Fuller would begin work on the Dymaxion Car.

What makes these homeless veteran shelters distinct from any other that Fuller was involved with was that they provided actual shelter to actual men. While they do not have the glamor of Fuller’s Dymaxion House and other creations, they hold the advantage of having existed. Giving a new purpose to an existing structure was an idea that Fuller seldom developed but never abandoned. In his 1970 book I Seem to Be a Verb, Fuller wrote: “Our beds are empty two-thirds of the time. Our living rooms are empty seven-eights of the time. Our office buildings are empty one-half of the time. It’s time we gave this some thought.”

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

Reference:

71st Infantry Regiment (New York). 1 April 2009. Wikipedia. 22 May 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/71st_Infantry_Regiment_(New_York)

Davis, Edwards: “Advocates the Standardizing of Industry by Law.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 27 July 1913: SM14

Fuller, R. Buckminster. I Seem to Be a Verb. New York: Bantam Books, 1970.

Ingersoll, Raymond V. Houses. 2009. New York City Housing Authority. 22 May 2009. http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/developments/bklyningersoll.shtml

“Louis Gleich, 69, Dies.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 26 Sept 1961: 39.

“Philip H. Hiss 3d, 78, Designer of Buildings.” New York Times [New York City, New York] 4 November 1988: B4.

Sieden, Lloyd S. Buckminster Fuller’s Universe. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing, 1989.