Buckminster Fuller Bibliography

Buckminster Fuller Bibliography by Trevor Blake.

One thousand five hundred entries by and about Buckminster Fuller. Books, magazines, newspapers and ephemera published between 1914 and 2015.

Richard Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller (1895 – 1983) was a public speaker, author, mathematician and inventor. Fuller is best known as the popularizer of geodesic domes in architecture. He attempted to apply the most recent discoveries of science to the most basic of human needs such as shelter and transportation, without regard for precedent or profit or power, doing more with less. He called this process design science.

Paperback

260 pages

Introduction, Bibliography, Index

$17.50

ISBN 978-1944651022

Buckminster Fuller’s Ultra-Micro Computer

Published on 12 July 2014, Fuller’s 119th birthday.

See also: Buckminster Fuller and the Twelfth of July.

“Never show half-finished work.” So said R. Buckminster Fuller in the March 1960 issue of Architectural Design. By the time the phrase “never show half-finished work” appeared in his book Critical Path (1981), “Universal Requirements Checklist” had been renamed “Comprehensively Anticipatory Design Science’s Universal Requirements for Realizing Omnihumanity Advantaging Local Environmental Controls, Which are Omniconsiderate of Both Cosmic Evolution Potentials and Terrestrial Ecological Integrities.”

The evolution of the simple “Universal Requirements Checklist” to “Comprehensively Anticipatory Design Science’s Universal Requirements… ” is representative of Fuller’s process. Fuller’s ideas grow more complex each time they are presented, sometimes obscuring the original idea. But if you can find your way to that central early idea, there is often something of great value.

Everything is equally connected to everything in Fuller’s writing. Fuller was unable to speak of mathematics, ethics, his individual life, global distribution of goods and services - everything - without speaking of all of it. You’d recognize it as the way crazy men talked, if crazy men were courted by publishers and universities all over the planet, and if crazy men earned dozens of ground-breaking patents, and most of all if crazy men and their crazy ideas didn’t turn out to be merely decades ahead of their time. I have some half-finished work by Fuller in which he clearly states an idea decades ahead of when he said it. I also have the finished work, still ahead of its time but nearly impenetrable in how it is presented.

The clearly stated work is a transcription of a recording Fuller made in the late 1960s. The transcriptions reside in Box 9, Folder 3 of the Stanford University Special Collection of R. Buckminster Fuller. The transcriptions document a series of discussions between Fuller and his patent attorney, D. Verner Smythe. The patent was not pursued and does not appear in Inventions, Fuller’s book of patents. The subject of the patent does, however, appear in Fuller’s magnum opus, Synergetics (1975 and 1979). To understand a node of Fuller’s thought requires tracing an idea across many other nodes of Fuller’s thought. But by tracing a line from diary entries through transcribed monologues through published books, Fuller is shown to predict atomic-scale computers nearly forty years before today’s discussion of graphine semi-conductor computers.

The nucleus of Fuller’s story is a simple diary entry from 1 February 1928: “after much philosophical thought while walking about worked out theory of spheres.” By 1939, in a letter intended for publication to Joe Bryant, the walking about had been expanded upon. Now there were thoughts of suicide and murder, a mugging that broke Fuller’s cheek bone (never otherwise confirmed), and a disembodied voice that told him: “You think truthfully. From now on, you need never await temporal attestation to your thoughts.” By the 1970s the story included Fuller floating in the air, surrounded by a sphere of light. Fuller’s story pulses, from an amateur consideration of geometry to a blessing from the hand of God and back again.

Fuller’s theory of spheres is a synthesis of established mathematics, personal insights and numerology. His theory of spheres is a thought experiment that can be reproduced with physical models. Imagine a single sphere floating in space. Add another to it, and a third so that all three are touching each other. Add another sphere that touch only the first two so that the center of each sphere is on a plane. Add a fifth and a sixth sphere, both touching the initial sphere and its neighbor, and the result is six spheres around one. Three more spheres can be nested in the six spaces above and below the plane such that they touch the initial sphere and two of their neighbors.

illustrations Copyright (c) 1975 the Estate of Buckminster Fuller.

IF three spheres nested below are staggered so that they alternately nest above and below the plane, the center of every sphere is an equal distance from all of its nearest neighbors, all spheres are an equal distance from the central sphere, and lines drawn from the center of all external spheres to their external neighbor form a cuboctahedron. A cuboctahedron is a polyhedron made up of eight triangular faces and six square faces. It can also be viewed as four interlocking hexagons, or a faceted globe with triangular poles and a hexagon equator.

Sphere-packing is an idea as old as the first stack of cannonballs or oranges. But Fuller’s theory of spheres led to a discovery that is unique. A tetrahedron made with ridged struts and flexible joints will hold its shape even when pressure is applied to a strut or a joint. Most other similarly constructed polyhedron will collapse under pressure. The cuboctahedron will also collapse, but in an interesting way. If pressure is applied to opposing triangular sets of struts, the hexagon between them will ripple. The struts double and form an octahedron (eight triangular faces). Between the cuboctahedron and octahedron, an implied icosahedron polyhedra (twenty sides) can be seen. And with a little hand work, the octahedron can be twisted into a triple-strutted tetrahedron. Fuller called this the “jitterbug transformation” and it is a mathematical insight that is his alone.

Having discovered the jitterbug transformation, Fuller considered it signficant and needed to find a use for it. He made a cuboctahedron cage of curved wire and rotated it on a globe until the wire least overlapped land masses. The cuboctahedron was the basis of his first Dymaxion Projection Map. The cuboctahedron was also the basis for Fuller’s earlier geodesic domes. In Fuller’s earlier geodesic domes a cuboctahedron was puffed up into a sphere, with the triangular and square faces faceted into smaller triangles and squares. Some of the lines that make up the faces run nearly all the way around such a sphere, and these Fuller called great circuits. The great circuits are the struts on Fuller’s earlier geodesic domes. Later he switched to “type two geodesic domes” based on the icosohedra, and an icosohedron based Dymaxion Projection Map. But he never abandoned his attraction to the cuboctahedron. He used it as a symbol for his mail order business in Philadelpha in the early 1980s.

Sphere packing (or as Fuller called it, the closest packing of spheres) twelve around one creates an implied cuboctahedron. If more spheres are placed around cuboctahedron, a larger cuboctahedron is formed. Every new layer of spheres makes a more sharply angled cuboctahedron, never a sphere. With one sphere in the center, the first layer has 12 spheres. The second layer will hold 42 spheres, the third layer 92, the fourth layer 162 and the fifth layer 252. All of these layers and every layer following ends in the number two. Round the number of spheres in a layer (10, 40, 90, 160, 250) and divide the numbers by ten and a progression by the second power is revealed (1, 4, 9, 16, 25). This is also an original discovery by Fuller.

The discovery could not be left as it was found. Fuller’s style of closest packing of spheres could not just be, it had to be meaningful. Adding the number of spheres in the first, second and third layer of spheres around a nucleus sphere (12 + 42 + 92) yields 146 spheres. This is the number of neutrons in the element uranium. Add 92 to 146 to yield 238, the number of neutrons and protons in the element uranium. From this numerological correspondence Fuller concluded that his style of sphere packing was descriptive of the structure of atoms, and thus all matter.

The cuboctahedron as a model for all matter, even this was not inclusive enough for Fuller. He imagined ideas were spheres. Not that spheres are a model for ideas, but that ideas were physical spheres. Some ideas are too specific to be of importance and some ideas are too general to be of importance. Ideas that are too specific are small spheres and ideas that are too general are large spheres. Small idea spheres will cluster around a center, large idea spheres will be pushed further from a central point. One idea is a free-floating nothing, two connected ideas might suggest something worth pursuing, three connected ideas point to a pattern, and four connected ideas form a tetrahedron. A tetrahedron of ideas will include ideas relevant to each thought and exclude irrelevant ideas, because a tetrahedron is the most simple polyhedron that has an inside and an outside (after spheres, I might add). Thus it takes four ideas to make a thought, and the shape of a thought is thus a tetrahedron. Fuller’s theory of spheres was a description of all matter and all consciousness.

These are examples of how Fuller’s thoughts breathed in and out, pulsed and jumped, danced a jitterbug. There was no clear demarkation line between established mathematics, numerology, personal biography, original insights, physical models and cosmic truths. There are good reasons to try and tease out what was original to Fuller and what he took from others, what is actionable and what is ornamentation. One of those good reasons is to speak plainly of when Fuller was decades ahead of his time, because sometimes Fuller was his own worst promoter.

In 1968 and 1969 Fuller met with his attourney Dale D. Klaus. The meeting was a monologue in which Fuller initiated a patent tentatively titled “Energy Systems for Computer Memory.” The trancribed meeting was combined with pages from the 1955 manuscript of what would later be published as Synergetics and Synergetics II. Fuller said his new kind of computer memory would differ from all existing computer memory:

Instead of having linear arrangements which is the way they tend to do things - linear and matrix array, I could do it omnidirectional phenomenon.

Fuller’s computer is a layered cuboctahedrons, each layer made of spheres. Fuller describes the spheres as glass coated with gold, silver, copper or aluminum depending on their location in the array. But Fuller also speaks of individual atoms of these materials, predicting by decades the nanocomputers under development today.

These layers of cuboctahedrons would have arrays of hexagons on their equators, and the nanocomputers of today are made of layers of hexagons. The fifth layer of a layered cuboctahedron of spheres would have the potential for a new nucleus sphere.

Conventional ciruits are described by Fuller as computing in a flat, ninety-degree, x/y array. Fulller’s computer would function in three dimensions at both sixty-degree and ninety-degree angles. The Fuller computer would begin a process with an electric impulse to the central, nucleus sphere. That signal would radiate out in all directions to the surrounding spheres. The radiating signal would terminate based on the strength of the signal, the material of the surrounding spheres, and the distance of a sphere from the nucleus sphere. The pattern of where the signal terminated constitutes stored information. Fuller speaks of his computer as made up of coated glass spheres, but also as single atoms of different elements.

I can lead a wire into one of the spheres at the center of the system and give that a load - and it would have to go out through it’s 12 contact points and by the frequency I give it I am sure I could round a special layer. […] I am planning to have a conductor to the center of the mass of atoms. There would be one atom that makes contact, we wouldn’t even have to see it. Well, the balls, the atoms by the time we get thorugh all the electrons actually have the same… we find with the electron microscope they look just like the same spheres. So by giving the right frequency and going out the right radial distance from there and pick up that information from millions and millions out there at that particular layer.

Three great circles could be done in gold, the four great circles could have been done in silver, the six great circles could have been done in copper and the twelve great circles could be done in aluminum. Now they are all conducting but they are all quite different.

Now about layers. If I were making this myself, say in ping-pong ball size, I couldn’t have very many layers. I figure in this room here I could have 100 layers or so. But if I were to use it… once I made this model then we would know this is exactly the same model as the closest packed spheres, as atoms. So then I would be able to assume millions of layers around a given atom.

Not all atoms but most atoms are packed that way […] So now we would be able for a given frequency… we would know how many special case informations we have stored there and how many relationships there are. […] There is no absolute continuum anyway so even those gold atoms… they happen to be closest and they will simply go from one to the other. But their resistances come in here, too. You will find there is a jump, there is a little jump from atom to atoms. A quantum jump.

There is a resistance difference due to the vertexes they go through. There is a resistance differential. Information can be stored in layer after layer and I think this is a storage system if you talk about compactness, there is nothing to compare it to.

I have re-arranged some of the above quotes to join like ideas, but I have not otherwise edited what Fuller said. His thinking-out-loud is not made up of complete and actionable ideas, but it does clearly point to an atom-sized hex-based system of computer memory. This is identical to the graphine memory systems now under development.

Compare the above rough take on Fuller’s computer with the following description as found in Synergetics:

I am confident that I have discovered and developed the conceptual insights governing the complete family of variables involved in realization by humanity of usable access to the ultimate computer… ultimate meaning here: the most comprehensive, incisive and swiftest possible information-storing, retrieving, and variably processing facility with the least possible physical involvement and the least possible investment of human initiative and cosmic energization. […] We have here the disclosure of a new phase of geometry employing the invisible circuitry of nature. The computer based on such a design could be no bigger than the subvisibly dimensioned domain of a pinhead’s glitter, with closures and pulsations which interconnect at the vector equilibrium stage and disconnect at the icosahedron stage in Milky-Way-like remoteness from one another of individual energy stars. […] The atomically furnished isotropic vector matrix can be described as an omnidirectional matrix of “lights,” as the four-dimensional counterpart of the two-dimensional light-bulb-matrix of the Broadway-and-Forty-second Street, New York City billboards with their fields of powerful little light bulbs at each vertex which are controlled remotely off-and-on in intensity as well as in color. Our four-dimensional, isotropic vector matrix will display all the atom “stars” concentrically matrixed around each isotropic vector equilibrium’s nuclear vertex. By “lighting” the atoms of which they consist, humans’ innermost guts could be illustrated and illuminated. Automatically turning on all the right lights at the right time, atomically constituted, center-of-being light, “you,” with all its organically arranged “body” of lights omnisurrounding “you,” could move through space in a multidimensional way just by synchronously activating the same number of lights in the same you-surrounding pattern, with all the four-dimensional optical effect (as with two-dimensional, planar movies), by successively activating each of the lights from one isotropic vector vertex to the next, with small, local “movement” variations of “you” accomplished by special local matrix sequence programmings. We could progressively and discretely activate each of the atoms of such a four-dimensional isotropic vector matrix to become “lights,” and could move a multidimensional control “form” through the isotropic multidimensional circuitry activating field. The control form could be a “sphere,” a “vector equilibrium,” or any other system including complex you-and-me, et al. This multidimensional scanning group of points can be programmed multidimensionally on a computer in such a manner that a concentric spherical cluster of four-dimensional “light” points can be progressively “turned on” to comprise a “substance” which seemingly moves from here to there. […] The ultra micro computer (UMC) employs step-up, step-down, transforming visible controls between the invisible circuitry of the atomic computer complex pinhead- size programmer and the popular outdoor, high-inthe-sky, “billboard” size, human readability.

The above quotes are from “Nuclear Computer Design,” section 427.00 of Synergetics. This is the same section in which Fuller suggest in antiquity humans were scanned atom by atom at a distant location and teleported to Earth by radio frequencies.

Teleportation aside, compare Fuller’s description of hexagon-based layered computer systems described in 1968 with these recent press releases…

- Multi-layer 3D graphene transistor breakthrough may replace silicon.

- New form of graphene allows electrons to behave like photons.

- All-graphene computer chip could steer us past the 22nm copper and silicon bottleneck.

- IBM builds graphene chip that’s 10,000 times faster, using standard CMOS processes.

It would sound like so much crazy talk, were he not also talking (in a byzantine way) of technologies the world is discovering to be true decades after Fuller described them.

SOURCES (Chronological)

Fuller, R. Buckminster: “Unviersal Requirements Check List.” Architectural Design March 1960.

Fuller, R. Buckminster: “Energy Systems for Computer Memory.” Unpublished manuscript 1968-1969.

Fuller, R. Buckminster: Synergetics. Macmillan Publishing Co. 1975.

Fuller, R. Buckminster: Synergetics II. Macmillan Publishing Co. 1979.

Fuller, R. Buckminster: Critical Path. New York: St. Martin’s Press 1981.

Lorance, Loretta: Becoming Bucky Fuller. Cambridge: MIT Press 2009.

Trevor Blake is the the author of The Buckminster Fuller Bibliography and The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller.

The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller - Kindle Edition

Addendum 2016: The complete contents of “The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller” have now been published for free at synchronofile.com.

See BOOKS for more information on Buckminster Fuller Bibliography and other books.

Buckminster Fuller Bibliography - Kindle Edition

Addendum 2016: See BOOKS for more information on Buckminster Fuller Bibliography and other books.

Fuller in Fashion

Fashion is design you wear, mobile and kinetic, including both tension and compression components. Fashion is the valve between the environment (everything except you) and the universe (everything including you). R. Buckminster Fuller’s influence on fashion is an undocumented parallel to his investigation into design.

☂ Fuller was attentive to his appearance. In Your Private Sky (Baden: Lars Muller Publishers 1999), Fuller is quoted as saying:

I decided to make a complete experiment of peeling off from society in general, and started wearing T-shirts which nobody was doing then, went about without a hat and in sneakers - absolutely comfortable clothes. Then when people started getting interested in my Dymaxion House, very nice people with influence, and they’d say, “l’d like to give a dinner party for you” and so forth, I would show up in khaki pants and they’d be very shocked. And when Mrs. John Alden Carpenter, head of the Arts Council in Chicago, gave a beautiful dinner party, I showed up and rudely announced, “I don’t eat that kind of food,” and was in every way obnoxious. l was putting self and comfort ahead of my Dymaxion House, and I said, “You’re not allowed to do that. You must get over that. You must stop that looking eccentric, with everybody pointing at this guy.” So I decided the way to do that was to become the invisible man, and that means a bank clerk - so I put on a black suit, bank clerk’s clothing; then they would focus on what I was saying instead of my eccentricities. I said, “I must get rid of continually making too much of myself.”

Fuller also knew of the attraction of the nude. When he exhibited the Dymaxion House in the 1920s, he placed a nude doll in its bedroom.

☂ Continuum Fashion is the source for this graphic showing one of a pair of irregular geodesic hemispheres…

The graphic is a glimpse into the mathematics of the N12, a bikini designed with a 3-D scanner and printed with a 3-D printer. Continuum writes:

The N12 bikini is the world’s first ready-to-wear, completely 3D-printed article of clothing. All of the pieces, closures included, are made directly by 3D printing and snap together without any sewing. N12 represents the beginning of what is possible for the near future. N12 is named for the material it’s made out of: Nylon 12. This solid nylon is created by the SLS 3D printing process. Shapeways calls this material “white, strong, and flexible”, because its strength allows it to bend without breaking when printed very thin. With a minimum wall thickness of .7 mm, it is possible to make working springs and almost thread-like connections. For a bikini, the nylon is beautifully functional because it is waterproof and remarkably comfortable when wet.

☂ “When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.” This quote is attributed to R. Buckminster Fuller but I cannot find the source. More significantly, the greatest online biographer of Fuller - Joe S. Moore at his incredible buckminster.info - also cannot place this quote. Can you?

☂ Photographer Moria Simmons and a friend went as “Buckminster Fuller and the Geodesic Dame” on Halloween 2008. See Moria’s photograph here, and more of her photography (including a sneaky shot of the Dymaxion Car and the Fuller postage stamp) here. Could this be the same Moria who knitted a geodesic hat?

☂ Laura Dawson is a fashion designer. She used a geodesic dome to exhibit her Fall 2009 collection. (Thanks to grunch.net).

☂ The Buckminster Fuller Institute sells handbags and if memory serves they have sold pins and t-shirts in the past.

☂ Colleen Coghlan designed an inflatable type-two two-frequency geodesic pillow dome garment. She writes: “The inflatable dress (or ‘Wearable Space’) is, as the name describes, a garment that inflates into a personal space to sleep, rest or play within.”

Read more about the Wearable Space at The Cool Hunter.

☂ Connie Chang Chinchio sells a pattern for a geodesic cardigan.

☂ Life Magazine could have published a photograph of anyone assembling a Dymaxion Map in March 1943. They chose a contortionist in her circus uniform.

☂ Fuller Houses by Federico Neder (Baden: Lars Muller Publishers 2008) includes several items of Fuller fashion. The color plates section in the rear of the book shows a lapel pin of the Dymaxion House, presumably sold in the Henry Ford Museum where the Dymaxion House is on display. Fuller Houses also includes a sketch of a Dymaxion Hat designed by Irene Sharaff.

☂ The umbrella is a favored icon at synchronofile because it is a portable relatively inexpensive dome shelter produced on the industrial level. There are endless variations to the umbrella, from a banker’s basic black to the LED umbrellas of the film Blade Runner. The Bucky Bar was raised in February 2010. It was a geodesic dome made up of umbrellas designed by DUS Architects as a spontaneous (and unauthorized) dance bar in Rotterdam.

☂ Hair stylists Andreas and Markus contributed a two-frequency type two geodesic sphere hair weave to a fashion shoot by Purebred Productions.

☂ Florida-based Emilie produces beaded jewelry informed by energetic-synergetic mathematics.

☂ My first tattoo, which I gave myself around 1989, is a geometric shape referencing the work of Buckminster Fuller. No photographs of my tattoos have ever been published.

☂This essay first published on the twelfth of July 2011, a day of great significance to Buckminster Fuller.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

R. Buckminster Fuller’s Influence on Science Fiction Films and Television

R. Buckminster Fuller’s influence on science fiction films and television during his lifetime (12 July 1895 – 1 July 1983).

First Spaceship on Venus

[Wikipedia] [IMDB] [youtube]

1960. Film. Directed by Kurt Maetzig. Based on the novel The Astronauts by Stanisław Lem. An international rocket crew finds geodesic domes on the planet Venus.

Earth II

[IMDB]

1971. Television. Directed by Tom Gries. A space station makes a claim for independence from the Earth it orbits. R. Buckminster Fuller is credited as the “Technical Advisor for Earth” in Earth II. Fuller’s Dymaxion Map is used to track orbiting satellites in an Earth-bound control room.

Slaughterhouse 5

[Wikipedia] [IMDB] [youtube]

1972. Film. Directed by George Roy Hill. Based on the novel Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Billy Pilgrim is kept in a geodesic dome in a zoo on the planet Tralfamadore.

Silent Running

[Wikipedia] [IMDB] [youtube]

1972. Film. Directed by Douglas Trumbull. The spaceship Valley Forge includes several geodesic domes.

The Starlost

[Wikipedia] [IMDB] [youtube] [The Starlost: The Word]

22 September 1973 – 5 January 1974. Television. Directed by Leo Orenstein. Created by Harlan Ellison. Executive Producer was Douglas Trumbull of Silent Running. A geodesic dome from the spaceship Valley Forge from Silent Running is re-used on the spaceship The Ark.

Battlestar Galactica

[Wikipedia] [IMDB] [Battlestar Wiki: Agro Ship]

September 17, 1978 – April 29, 1979. Television. Created by Glen A. Larson.

The geodesic dome from the spaceship Valley Forge from Silent Running which had been re-used on the spaceship The Ark in The Starlost is re-used once more on an Argo Ship. This dome is on exhibit at the EMP Science Fiction Museum between 23 October 2010 - 4 March 2012.

See also LOST Domes.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

Synergetics Stew January 2009

The Buckminster Fuller Institute published the book Synergetic Stew: Explorations in Dymaxion Dining in 1982. Under this name, synchronofile.com publishes an irregular collection of brief notes relating to Buckminster Fuller.

☂ BLDGBLOG writes about the myriahedral projection map of computer scientist Jack van Wijk (Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands). “Making truly accurate maps of the world is difficult because it is mathematically impossible to flatten a sphere’s surface without distorting or cracking it. The new technique […] uses algorithms to ‘unfold’ and cut into the Earth’s surface in a way that minimizes distortion, and keeps the distracting effect of cutting into the map to a minimum.” Compare van Wijk’s work with Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map and with Butteryfly Map of Bernard Joseph Stanislaus Cahill.

☂ Speaking of Cahill, Gene Keyes has published a comparison of Cahill’s Butterfly Map and Fuller’s Dymaxion Map. Gene was a student of Fuller’s at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois. Nearly 40 years ago Gene wrote Bucky and Pick: Two Grand Designers of a World Without War. An Essay-Review of Robert Pickus (To End War) and R. Buckminster Fuller (Utopia or Oblivion). Fuller sent a handwritten letter to Norman Cousins (editor of Saturday Review) urging Cousins publish the essay. The essay has never been published - until now.

☂ The Imaginary Foundation is selling an “All-Star Pattern Seeker Trading Cards pay tribute to 23 giants of pattern recognition - pathfinders and ideanauts whose shadows loom large across three millennia of discovery. This set of 23 cards comes in a collectible embossed box.” Buckminster Fuller is one of the all-star pattern seekers so honored.

☂ Playboy Magazine mentions Fuller in the profile of Susan Miller (Miss September 1972) and an interview with Allen Ginsberg but some other Fuller information hasn’t made it online yet. This includes the Playboy article “Cities of the Future” from January 1968 and an interview from February 1972. Buckminster Fuller: Anthology for a New Millennium edited by Thomas Zung incorrectly cites Fuller’s Playboy interview in the year 1970. Fuller makes some remarkable claims in his Playboy interview… “I’m not surprised to see women getting naked, because the more naked they are, the more they tend to discourage the sex urge. If a woman is covered up with skirts, man is driven by curiosity. Take away the skirts and he says to hell with it. And I find us getting an enormous amount of homosexuality, which I see as nature supplying us a negative urge that diminishes our capacity to make babies.” “Man probably came to this planet as whole man, a creature very much like what we see today. He might have been sent by electromagnetic waves.” “You could take human beings and inbreed them until you came up with a monkey. You can see that happening every day. Lots of people are halfway to monkey.” See also Buckminster Fuller, Creationist.

☂ Science Daily writes that Salvatore Torquato (Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials) and Yang Jiao (Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering) have bested the world record set last year by Elizabeth Chen (University of Michigan) for tetrahedra packing. “Torquato and Jiao were able to fill a volume to 78.2 percent of capacity with tetrahedra.” Buckminster Fuller made no specific claims about the closest packing of tetrahedra but would likely have found this discovery of interest.

☂ synchronofile.com had the honor of announcing the restoration of the Dymaxion Car in September 2009. This resulted in a spike of interest in the car both on and off the Internet (see below). Crosthwaite and Gardiner, the company trusted with the restoration, have published some remarkable photographs of their work in progress here and here. Your help is still needed in identifying the source components used in the original Dymaxion Car.

☂ Noel Murphy is filming a documentary titled The Last Dymaxion. “One of the greatest minds of our time designed the very first green car. Certain corporations destroyed the possibility of that car ever being produced, but now, in the 21st century, the last Dymaxion is being restored, and along with it Buckminster Fuller’s Dream.” Noel is also the author/lead in the play Buckminster Fuller Live. The Last Dymaxion is scheduled for release Christmas 2010.

☂ The 1929 automobile of Engelbert Zaschka exhibited features that were important to Fuller. It was a three-wheeled car, like his Dymaxion. But it could also easily be folded, disassembled and re-assembled as could Fuller’s Dymaxion House and many geodesic domes. Zaschka was an advocate and pioneer inventor for the personal helicopter, achieving Fuller’s goal of a personal omnidirectional transportation vehicle. More information at Wikipedia (English, German) German-language excerpt from a television documentary on Zaschka here and a short film of the Zaschka being disassembled here.

☂ Hillary Louise Johnson wrote Super Vixens’ Dymaxion Lounge in 1997. Chapters one through six of Super Vixens’ Dymaxion Lounge are now online. Salon described the book as “a slim but wickedly brutal take on existential life in modern L.A., and one woman’s quest for depth amidst the neon-drenched chaos and urban (not to mention urbane) sprawl. With a toddler in tow all the while. […] Much of the book focuses on Johnson’s search for a way past such hackneyed responses, but she’s also aware of how difficult that is in a town where, a friend tells her, ‘style is substance.’ L.A. is a ‘dymaxion’ town, a term used by Buckminster Fuller to describe a world unto itself, where everything intermeshes and everything is available. So she’s wise enough to know that the idea of breaking through clichés is a cliché itself. Is she really going to be gratified by seducing the Little Caesar’s delivery boy, dating a couple, hanging out with drag queens? Nothing’s ironic in a town built on irony; a teacher at a Montessori school placidly tells Johnson that ‘the playground’s in the backyard, very safe from drive-by shootings.'”

☂ D. W. Jacob’s play R. BUCKMINSTER FULLER: THE HISTORY (and mystery) OF THE UNIVERSE will be performed May 28 - July 4, 2010 at the Arena Stage Crystal City in Washington, DC. Doug tells me: “Crystal City has put out an international call for artists to create outdoor works of art around Bucky themes and concepts, etc.” More information available from the Arena Stage.

☂ Kirby Urner was the first webmaster for the Buckminster Fuller Institute (bfi.org circa 1996 via archive.org). His sites 4D Solutions and grunch.net were some of the first and best online for Fuller mathematics. He was a consultant for textbook publisher McGraw Hill and continues to serve as an educator. Kirby is involved in the Thunderbird Early College Charter School, IEEE, Leadership & Entrepreneurial Public Charter High School, python and linux development and much more. Sometimes Kirby openly promotes Fuller in his educational work, sometimes he works in stealth mode. See a little of both in action at the Oregon Curriculum Network. Kirby’s style is that of a river: as deep as it flows, it also flows swift. He’s on to the next problem before you dry off from the first. Try to catch up with Kirby via Grain of Sand, Control Room , Coffee Shops Network, and the BizMo Diaries. Each of these is generously illustrated with his flickr photo stream.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

Who Am I?

He was born in the 1800s. He conducted an extensive survey of world resources although he was not formally trained to conduct such a task. This survey of world resources demonstrated to him that the profit motive was getting in the way of the efficient and humanitarian distribution of goods and services. He advocated fully-automated factories, and wrote about energy consumption as the most accurate measure economic value. He was Howard Scott.

He was born in the 1800s. He crossed paths with Technocracy Inc. He wrote about the closest packing of circles. His mathematical work was not in essay form but in poetry. His work was ignored while alive but has influenced many (with and without credit) since his death. He was Frederick Soddy.

He was born in the 1800s. He was an inventor not only of a particular artifact for which he is well known for one, but more importantly of a new method of manufacturing and distribution. He wrote books on creating buildings so large entire cities could be housed inside, and the use of round houses laid out on hex-grid streets. He supported global economic reform based on technological competence rather than profit so that all human needs could be met at no cost to the recipient. He was King Gillette.

He was born in the 1800s. He invented a map of the world that received a United States patent. This map displays all continents in an uninterrupted way. The map can be folded into a globe. He designed a domed building. He was Bernard Cahill.

He was born in the 1800s. He became an inventor from an early age, a practice that never left him. An early death in his family also never left him. He investigated alternative fuel sources, innovative new toilets and octahedron-tetrahedron truss structures as an architectural form. Scientific discoveries have been named after him long after his death. He was Alexander Graham Bell.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com

The Lost Inventions of Buckminster Fuller (Part 1 of 3)

The Lost Inventions of R. Buckminster Fuller is a three-part investigation into the inventions of Buckminster Fuller. These essays can serve as companion essays for two previous books by and about Fuller: Inventions (Fuller, St. Martin’s Press 1983) and The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (Marks and Fuller, Doubleday 1973). Ownership of these two books is not necessary for reading these essays. Page numbers without citations are from Inventions Fuller made many claims about his inventions, claims which are confirmed or called into question by these essays. A new appreciation for Fuller’s innovations is the result.

Fuller claimed that his life goal was to provide humanity with the means to save itself from itself and from natural disasters. To that end Fuller could have given his inventions up to the public domain, making them more accessible to more people. But Fuller sought, obtained and defended patents for many of his inventions, for two reasons.

First, Fuller hoped that the long-term and public nature of the US Patent Office would serve as a long-term and public record of his work. Fuller wrote in Inventions: “The public record established by my patents […] can serve as a critical appraisal of the historical relevance, practicality, and relative effectiveness of my half-century’s experimental commitment to discover what, if anything, an individual human being eschewing politics and money-making can do effectively on behalf of all humanity.”

Second, Fuller hoped to prevent others from profiting from his inventions. Donald W. Robertson served as Fuller’s patent attorney and wrote about his experience in The Mind’s Eye of Buckminster Fuller (Robertson, St. Martins 1983). Robertson described why Fuller sought patents: “While Fuller did not wish to seek patent profits by selling efforts, he was adamant in seeking to forestall efforts of others to profit by making unauthorized use of his inventions.” Fuller defended his patent interests. Fuller’s archive includes legal disputes over royalties with North American Aviation between 1958 and 1961 and with Ernest Okress between 1978 and 1979. According to Siobhan Roberts’ book on mathematician Donald Coxeter, King of Infinite Space (Roberts, Walker & Co. 2006), Fuller’s patent on the Radome was defended in Canada by the United States Department of Defense. Fuller sought and sometimes obtained intellectual property rights in Argentina, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Columbia, The Congo, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Finland, France, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United State, the United Kingdom, Uruguay, Venezuela and West Germany.

All of Fuller’s inventions are lost in some way. All of Fuller’s U. S. patents are lost in that they have expired. Some of Fuller’s patents expired in his lifetime. This is due to his being unable to afford a renewal, or his deciding to let a patent expire, or perhaps neglect. Many of Fuller’s patents lost their references to earlier patents by other inventors. That is, what Fuller claimed he invented was in fact invented by someone else. Sometimes Fuller was ignorant of prior work, such as the octet-trus constructions of Alexander Graham Bell. Sometimes Fuller stole ideas whole-cloth, such Kenneth Snelson’s sculptures re-branded as Fuller’s tensegrity. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they have yet to go into production, existing only as scale models. Perhaps now that Fuller’s patents have expired some of them can be tested against Fuller’s claims. Perhaps the fog gun could be tested in arid environments, for instance. Many of Fuller’s patents are lost to the curious because they are not always filed under their popular name. The patent for the geodesic dome is to be found under the title ‘Building Construction,’ which has likely caused some researchers difficulty in finding it. Some of Fuller’s patents are lost because they are under-documented. Automobile restoration firm Crosthwaite and Gardiner had access to nearly all the information ever produced about the Dymaxion Car, but at times had to make their best guess in the creation of Dymaxion Car #4 because detailed schematics and photographs were not available. The credits to many of the illustrations in Inventions are lost. Illustrations appear in the book without further information. The photograph on the front cover is a 36-foot geodesic dome made by students at the University of Minnesota and assembled in Aspen, Colorado in 1952. Additional photographs of this dome can be found in Dymaxion World illustrations 334-339. The end papers show the paperboard dome of 1954. Page vi shows Fuller with a partially-assembled model of the 4D House in New York City in 1929. Page xi shows Fuller at Black Mountain College in 1948. Pages xvii and xviii appear to be Fuller at the Montreal World’s Fair dome. The photographs on pages xiv, xxvi-xxvii, xxxi and xxxii are of unknown origin.

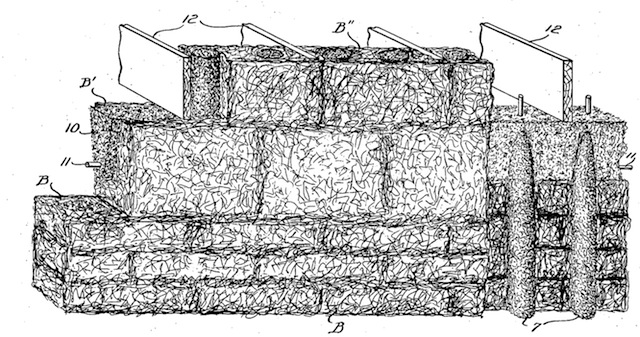

The Stockade Building Structure is a method of making bricks that have holes in them, and the method of sliding those holes over standing metal poles (a ‘stockade’). The Stockade Building Structure is called Building Structure in patent 1,633,702 (28 June 1927). It is patented by James Monroe Hewitt and Fuller. The Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process is called Mold for Building Blocks and Process of Molding in patent 1,634,900 (5 July 1927), awarded to Fuller. Fuller was the President of Stockade Building System Inc., according to Buckminster Fuller’s Universe by Lloyd Sieden. Becoming Bucky Fuller by Loretta Lorance offers the most complete account so far of Fuller’s complex relation to Stockade. In brief, Fuller’s father-in-law Hewitt gave Fuller a hand in the company in hopes Fuller could turn from drinking to supporting his daughter, Anne Hewitt. A companion photograph to the one on pages 2 and 3 of Inventions can be found on page 34 of Buckminster Fuller: An Autobiographical Monologue / Scenario by Fuller’s son-in-law Robert Snyder and illustration 9 from Dymaxion World. Fuller writes in Inventions that this process was invented by his father-in-law, Monroe Hewlett. This is confirmed by Hewlett’s earlier patents 1,604,097 (19 October 1926) and 1,450,724 (3 April 1923). Neither of these earlier patents appear in Inventions. Dymaxion World claims the Stockade System was “co-invented” by Fuller and Hewitt. Fuller writes in Inventions that “while I did much of the inventing of technologies, the [Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process] was the only one I felt was worth patenting.”

The Stockade Building Structure was co-invented by Fuller. The Stockade Pneumatic Forming Process was invented and patented by Fuller.

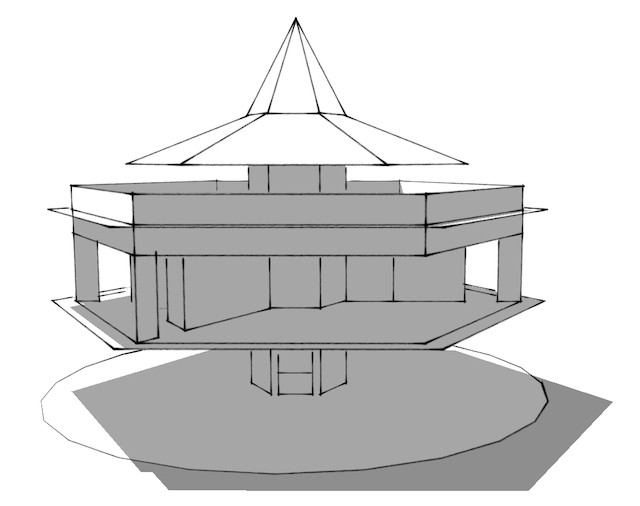

The 4D House is a house which, instead of resting on the ground, is suspended from a central mast. The 4D House has no patent. Inventions claims the patent was submitted in 1928, rejected, and Fuller did not re-submit out of ignorance that this was an option. Fuller does not state why he did not re-submit when he learned that this was an option. Inventions also claims the 4D House patent is rectilinear like a conventional house because his unnamed patent attorney advised him it would be more convincing to the patent examiners. The illustrations of the 4D House in Inventions are generally of a hexagonal building rather than the rectilinear building in the patent itself. Dymaxion World calls the hexagonal 4D House the “clean-up model” in illustration 40 and is seen in illustrations 40-41 and 49-64. Variations of the hexagonal 4D House are seen in Dymaxion World illustrations 2, 16-39 and 66.

In Buckminster Fuller’s Universe, Sieden writes that Fuller offered the rights to the 4D House to the American Institute of Architects as a gift and that this gift was rejected. According to Becoming Buckminster Fuller, Fuller was not ignorant of the patent process because he did pursue it before, at the time and afterwards. The patent for the 4D House was abandoned because of the 43 claims made in his application, all 43 could be found in earlier patents. Attorney D. H. Sweet is blamed for the rectilinear 4D House in his patent application but Fuller’s own sketches to this point had been rectilinear.

The 4D House is preceded by similar inventions.

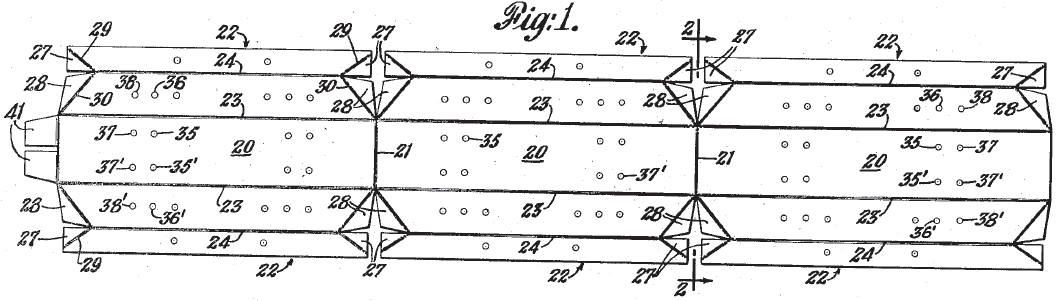

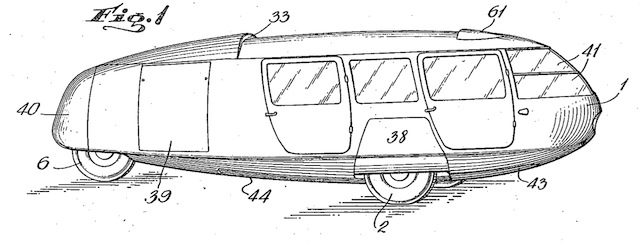

The Dymaxion Car is a three-wheeled automobile. The Dymaxion Car is called a Motor Vehicle in patent 2,101,057 (7 December 1937). The patent was assigned to Buckminster Fuller. Inventions includes the Great Britain patent for the Dymaxion Car. Fuller was the Director and Chief Engineer of the Dymaxion Corporation. The patent drawings most closely resemble Dymaxion Car #1, but two different Dymaxion Cars were produced and two more yet were conceived. In 2010, automobile restoration company Crosthwaite and Gardiner produced Dymaxion Car #4, based primarily on Dymaxion Car #2.

The photograph on pages 32-33 of Inventions shows Dymaxion Car #1 outside the Dynamometer Building of the Locomobile plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Locomobile produced cars from 1899 to 1929. This is the building that produced the first three Dymaxion Cars. The building was leased by W. Starling Burgess. Burgess produced a yacht in the building while contributing to the creation of the Dymaxion Car. The automobile in the upper left corner is a Franklin. Artist Diego Rivera is seen between the car doors with his jacket in his arms.

The earliest newspaper and magazine articles on the subject tend to favor W. Starling Burgess as the main force behind the Car. The Dymaxion Car is first mentioned in print in the New York Times on 1 June 1933. It is described as the creation of W. S. Burgess. The last sentence of the article reads: “Buckminster Fuller, New York architect and engineer, is associated with Mr. Burgess in the project.” By 22 July the New York Times comes to describe Fuller as the inventor of the Dymaxion Car and Burgess as the designer. The magazine Modern Mechanix of October 1933 lists Burgess and Fuller as co-designers of the Car. On 22 October the New York Times described the vehicle as the “streamlined, three-wheeled Gulf-Dymaxion Car, designed by W. Starling Burgess and Buckminster Fuller.” At the time, Gulf Oil had purchased advertising space on the side of the Car. Dymaxion World describes Burgess as “an assistant” in the project.

The Morgan Motor Company had been producing three-wheeled vehicles in the USA since 1909. The Burney, produced by Streamline Cars, used aviation design principles as early as 1927. The Chrysler Airflow was a streamline, drag-reducing car of 1934, as was the Tatra T77 of 1935.

The Dymaxion Car is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them. The public record initially credits Burgess as the inventor of the car, then credits Burgess as a co-inventor with Fuller, then Fuller in the lead with Burgess as an assistant, and finally Fuller alone.

Fuller seems to have had some role in the development of disc brakes during his employment at Phelps Dodge in 1937. Buckminster Fuller’s Universe describes Fuller’s invention as “a revolutionary solid bronze drum fitted with rubber insets to dissipate heat very rapidly, thereby solving [problems] which had plagued automobile and truck breaking systems for decades.” His new breaks also cut stopping times by nearly 50 percent and were the forerunner of the now-popular disc breaks. Grunch of Giants describes this invention as “carbon blocks-inserted, copper disc-brakes” that were “successfully demonstrated” in 1937. BuckyWorks claims that Fuller had considered disc brakes for the second Dymaxion Car (circa 1934). Fuller’s contribution to disc brakes is underdocumented.

Another 1937 Phelps Dodge invention of Fuller was a bunsen-burner-melted, water-cooled centrifuge for processing low-grade tin ore. This is mentioned in Grunch of Giants but does not appear in Inventions or Dymaxion World. What this invention might be and its impact on the world has yet to be documented.

The Fog Gun is a misting showerhead. The Fog Gun appears in Dymaxion World illustration 88-92 but not in Inventions. Grunch of Giants claims the Fog Gun was designed in 1927 and prototyped in 1949. Dymaxion World, Buckminster Fuller’s Universe and other sources quote Fuller claiming that while in the Navy he was able to clean grease off his hands by the mist eternally surrounding ships at sea. The fog gun is mentioned in Fuller’s 1938 book Nine Chains to the Moon. The fog gun was a means of directing atomized water under pressure for hygiene purposes. Dymaxion World claims the fog gun was tested at the Institute of Design in Chicago in 1948 “and subsequently at Yale and other universities.” In these tests a one-hour “massaging pressure bath” used one pint (.47 liters) of water. In session 11 part 2 of Fuller’s 42-hour lecture “Everything I Know,” Fuller claims professional dermatologists were consulted in researching the fog gun. Dymaxion World continues by saying “If fog gun bathing were done in front of a heat lamp, [all the effects of bathing] could be effected without the use of any bathroom. Since there would be no run-off waters, tons of plumbing and enclosing walls could be eliminated, and bathing would become as much an ‘in-the-bedroom’ process as dressing.” Buckminster Fuller’s Universe claims the test of the fog gun found it to be “a completely satisfactory system of cleansing, which, in fact, caused less damage to skin than ordinary soap and water. Thus, another significant artifact was created and left until a time when future generations would require it.” There is no record of Fuller seeking a patent for the Fog Gun.

The James Dyson Award is an international student design award with the challenge to “design something that solves a problem.” An uncredited Malaysian entry in 2011 describing a Mist Washer reads:

A mist nozzle inside the basin can produce mist which is mixture of water and soap to wet our hand. Later, water nozzle will spray water with medium velocity to clean our hand. […] High velocity water can helps in cleaning our hands, like the high pressure jet that we use in industrial for cleaning purpose, but in a small scale and lower pressure. […] Compare to common water tap, it is more clean and convenient because the user will never contact to the tap which had a lot of bacteria. […] There are only 1% of water is clean, it will be a serious issue in the future about the usage of water. So, this mist washer can reduce the usage of water to minimum because of the high pressure water nozzle. Compare to common water tap, mist washer is more environmental friendly.

Fuller’s Fog Gun is an invention whose generation may have arrived.

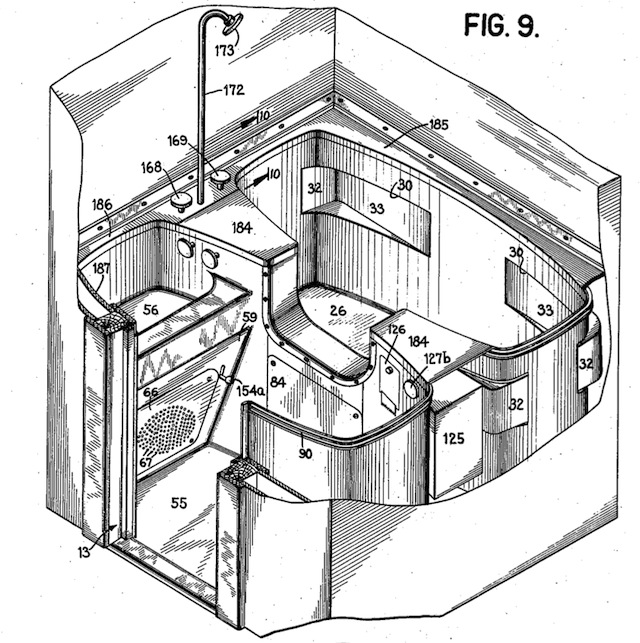

The Dymaxion Bathroom is a metal one-piece bathtub, sink and toilet. The Dymaxion Bathroom is called a Prefabricated Bathroom in patent 2,220,482 (5 November 1940). Grunch of Giants claims the Dymaxion Bathroom was designed in 1928, prototyped in 1936 and “mass-produced in polyester fiberglass in West Germany, 1970.” In 1936, Phelps Dodge wanted to expand their operations from mining copper to manufacturing copper products. Fuller was hired by Phelps Dodge as a director of research and allowed to pursue any area of interest he chose. Among his work for Phelps Dodge was the Dymaxion Bathroom. Earlier patents for a prefabricated bathroom include Orville Smith’s 2,131,124 (30 October 1938), Samuel Samelow’s 2,087,121 (13 July 1937), Ralph Otwell’s 1,931,392 (17 October 1933), Owen Ayer’s 1,763,209 (10 June 1930) and others.

The Dymaxion Bathroom is preceded by similar inventions, although there is no indication that Fuller was aware of them. In Dymaxion World, Fuller claims that the use of red and blue handles to indicate hot and cold running water comes from the Dymaxion Bathroom. Fuller did not claim to invent chemical toilets but he did suggest that the Dymaxion Bathroom could package waste to be picked up with other household waste and re-used by industry. This suggestion precedes the popularity of curbside recycling by decades.

The Mechanical Wing was a trailer-drawn mobile home, described in the October 1940 issue of The Architectural Forum. The Mechanical Wing included Fuller’s Dymaxion Bathroom and Fog Gun as well as the usual amenities of a mobile home. In Dymaxion World Fuller emphasizes that his invention was the cylindrical metal A-frame trailer of the Mechanical Wing, an invention later “popular as a trailer frame for transporting boats.” A similar A-frame trailer had been patented by P. L. Melanson in 1930 as Trailer for Vehicles (1,779,887).

The Mechanical Wing is preceded by a similar invention, but there is no indication Fuller was aware of it.

The Dymaxion Deployment Unit is a grain bin repurposed as a human shelter. The Dymaxion Deployment Unit (sheet) is called a Building Construction in patent 2,343,764 (7 March 1944). The Dymaxion Deployment Unit (frame) is called a Building Construction in patent 2,351,419 (13 June 1944). Fuller was the Director and Chief Engineer of the Dymaxion Corporation. Dymaxion World illustration 167 identifies the photograph on pages 54-55 of Inventions as having been taken in Haynes Point Park, Washington DC in April 1941. The photograph on page 61 of Inventions appears again with an exterior shot in Dymaxion World images 163 and 164. The photograph on page 68 includes Walter Sanders (head of the Department of Architecture at the University of Michigan) and his wife. The couple lived in the DDU for an unspecified period of time according to Dymaxion World. Dymaxion World emphasizes that Fuller modified the roof of an existing grain bin, giving it a more curved surface. This modification appears to be the basis for Fuller’s claim to inventing the Dymaxion Deployment Unit.

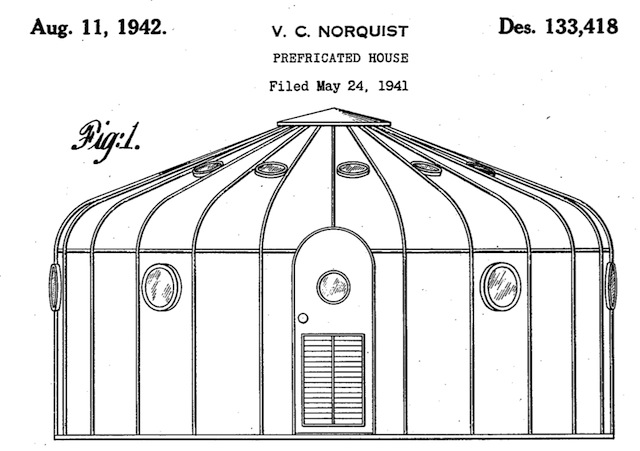

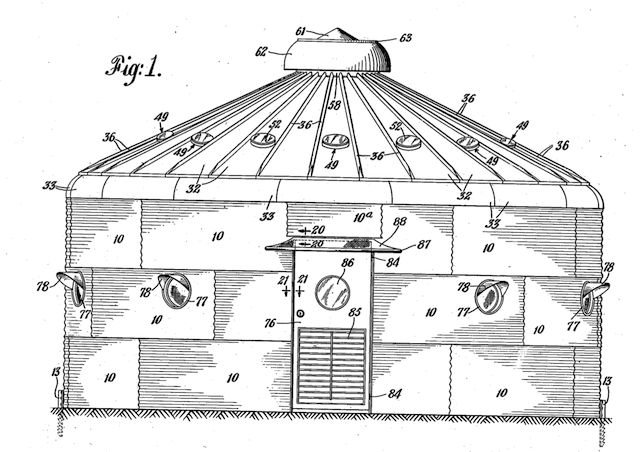

Two patents related to the Dymaxion Deployment Unit have a questionable history. Fuller’s Design for a Prefabricated House 133,411 does not appearing in Inventions. This patent is a near-identical copy of Design for a Prefabricated House 133,418 filed by Victor C. Norquist. Norquist had dozens of patents to his credit. Many of Norquist’s patents were assigned to Butler Manufacturing, which produced the Dymaxion Deployment Units. Norquist’s patent reads: “Be it known that I, Victor C. Norquist […] have invented a new, original and ornamental Design for a Prefabricated House of which the following is a specification… ” Fuller’s patent reads: “Be it known that I, Richard Buckminster Fuller […] have invented a new, original and ornamental Design for a Prefabricated House of which the following is a specification… ” The texts of 133,418 (Norquist) and 133,411 (Fuller) are nearly identical and the illustrations are nearly identical. Both patents are awarded on the same day, 11 August 1942. Norquist filed on 24 May 1941 and Fuller filed a week later on 31 May 1941. Norquist’s patent was awarded two years before either of Fuller’s Dymaxion Deployment Unit patents appearing in Inventions.

The Dymaxion Deployment Unit is preceded by similar inventions. Fuller’s patent is a copy of Norquist’s patent.

Fuller’s claim that zones of temperature influence history can be found in Life magazine for 1 March 1943. Fuller claimed that the major centers of industrial civilization lie within ten degrees of freezing, and this was the optimal temperature zone for human beings, and that as those who dwelled there were optimized they dominate the territories and people outside that zone. The Buckminster Fuller Institute wrote in 1992: “Buckminster Fuller then realized that: (1) the colder an area gets the larger the fluctuation in temperature is to be found, and (2) the more a geographical area’s temperature varies, the more technologically inventive must humans living there become in order to survive. (For example, they must learn to build boats to cross a lake in summer, as well as design sleds to cross the ice in winter.)” Fuller’s idea explains disparities in inventiveness and political success that does not rely on race, preceding Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond by fifty years. The peoples of Europe and Asia have more inventions and political success than those of Africa because there is more temperature variation in Europe and Asia than in Africa. In the past, temperature variation in Europe and Asia necessitated inventiveness that led to political and economic success.

Fuller’s zones of temperature explanation for historic disparities is unique.

The Dymaxion Profile of Industrial Revolution is a chart of technical progress and a proposed law for that progress. The Profile was first presented by Fuller in Washington DC in 1943. Fuller noted that the period of time between the identification of individual elements has decreased. Between the 1500s and the 1700s, only a dozen elements were identified. Starting in the 1700s, the number of elements identified increased rapidly. Fuller proposed that two laws of technological progress follow this geometric rise in the number of elements identified. First, as more elements are identified there are more technological discoveries and that these discoveries are also made with greater frequency. Second, discoveries follow a predictable trajectory from the laboratory to the home. In Dymaxion World Fuller describes the trajectory as “pure science paces applied science, applied science paces technology, technology paces industry, industry paces economics, economics pages the social, political, everyday catch-up.” In his 1936 book Nine Chains to the Moon, Fuller makes a similar claim in the chapter title ‘E=mc2=Mrs Murphy’s Horse-Power.’ The discoveries of Einstein, as abstract as they may be, will soon have practical applications in the household of an average American housewife.

- Trevor Blake

Trevor Blake is the author of the Buckminster Fuller Bibliography, available at synchronofile.com